Blahous: The Longer We Wait, the More Difficult It Is to Fix Social Security

Social Security trustee Charles Blahous has a interesting new commentary on the long-run sustainability of the Social Security program. The combined Social Security (OASDI) trust fund is due to be exhausted by 2033, but that measure, Blahous claims, gives the mistaken impression that we still have time to wait to make changes. He points out that the last major compromise on Social Security came in 1983, when the projected budget gap was much smaller than it is today (2.67 percent of payroll compared to 1.82 percent). And the shortfall has gotten larger in recent years, going from 1.91 percent to 2.22 percent to 2.67 percent over the last three reports.

1. The baby boomers are starting to retire. Lawmakers have historically been very reluctant to cut benefits for beneficiaries once they start receiving them. This means that any sacrifices will likely be concentrated on younger generations who already face net income losses through Social Security as it is. With every further year of delay lawmakers must therefore consider sharper benefit growth reductions and/or tax increases.

2. A solution requires substantial compromise by one or both sides. If one person (or a unified political party) commanded total political power and was willing to use it, they could impose their preferred solution on those who disagree. The last such opportunity was probably 2009-10 when Democrats controlled both chambers of Congress and the White House. Had they so chosen, they could have shored up Social Security on their own terms. No such attempt was made. Today no one expects that either party will single-handedly control the White House, the House, and 60 votes in the Senate within the next few years. Thus if Social Security finances are to be repaired, someone must dramatically compromise: either progressives must accept substantial benefit growth reductions, conservatives substantial tax increases, or both. Unfortunately as I will show below, we are already long past the point where there is precedent for a compromise of this magnitude.

3. There is a huge disparity between the problem’s urgency and the rhetoric applied to it by substantial factions of the body politic. Even as time is running out for a workable compromise, some continue to play a high-stakes gamble: that if the urgency is downplayed and action delayed past the next few elections, it can be dealt with when the political alignment may be more advantageous to one side. This gambit has now been extended to the point of imperiling Social Security’s long-term outlook. Too many key players, however, do not yet realize this.

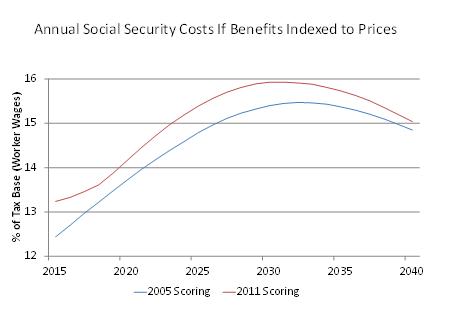

From a numbers standpoint, waiting to fix Social Security makes the task more difficult, since the fixes are becoming less and less effective. Removing the payroll tax cap would no longer ensure solvency for the program; similarly, indexing benefits that beneficiaries initially receive to prices rather than wages would no longer do the trick by itself. Blahous makes the point by showing how much the latter policy would save based on 2011 numbers compared to 2005 numbers.

Source: Charles Blahous

As you can see, the savings are smaller now than they were six years ago. Furthermore, the 2012 Trustees Report showed a deterioriation of Social Security's finances compared to 2011, meaning that the point is even stronger now. The recent trend has been worsening projections, so lawmakers may find themselves having to do more faster when they do get around to Social Security reform.

Blahous concludes that waiting much longer will likely result in Social Security needing to be funded from general revenue, if scheduled benefits are to be maintained. This would harm the contributory and self-financing nature of Social Security, as its creators initially intended. He notes that this approach would be at odds with what Social Security advocates want, forcing it to compete with other programs for funds.

The main point, of course, is for lawmakers not to wait to enact a Social Security plan. Doing so will allow for less drastic changes and allow time for lawmakers to phase them in, thus giving beneficiaries time to plan. Reform is only going to get harder the longer we wait.

To see how budget plans would change Social Security, check out our comparison grid.