President Trump's Historic Debt Dilemma

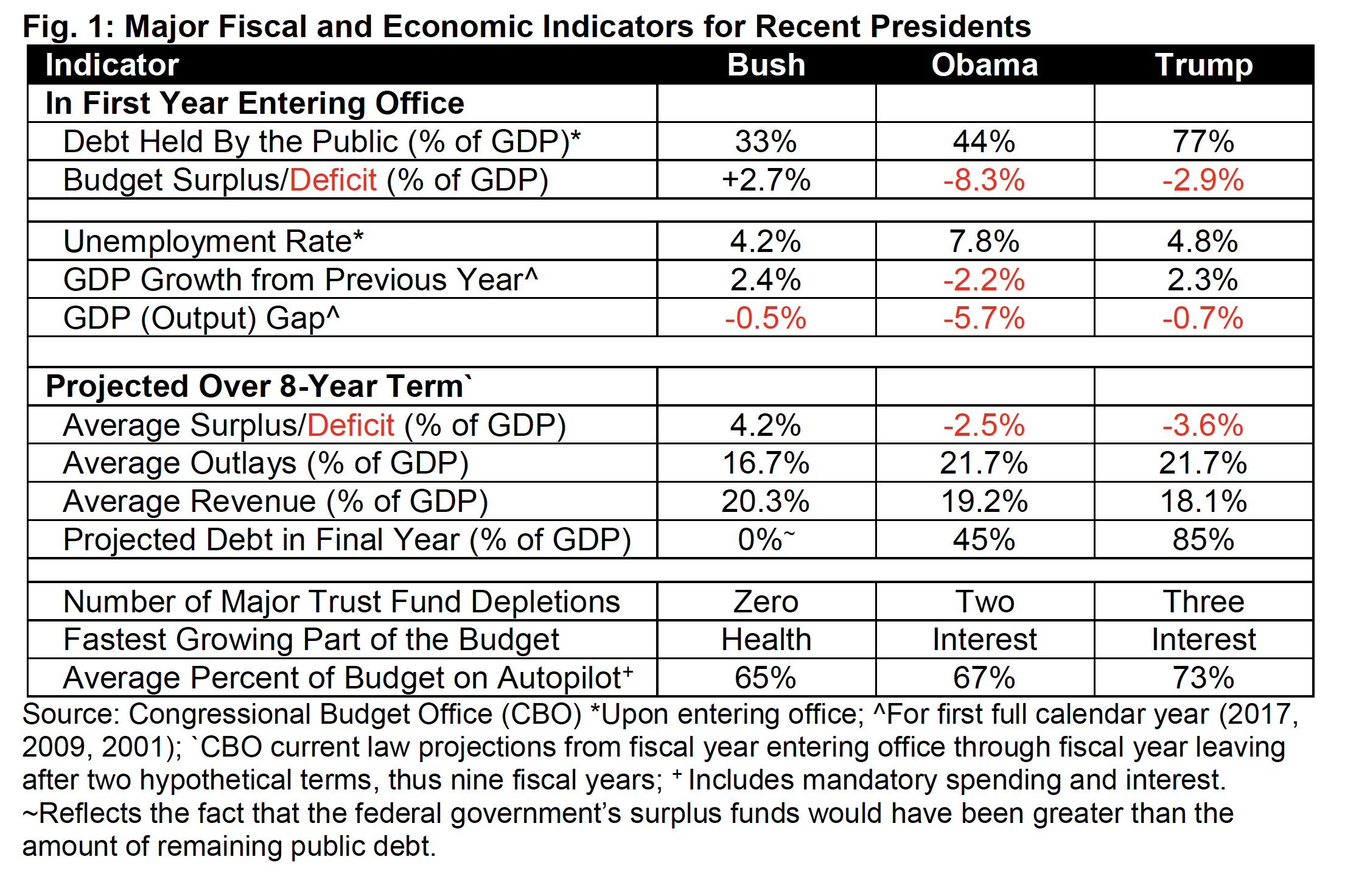

As President Donald Trump begins his term, he faces perhaps the most daunting fiscal situation of any incoming president. President Trump enters office with high levels of debt, rising deficits, major trust funds facing shortfalls, and no agreement on how to address these challenges. In this paper, we show that:

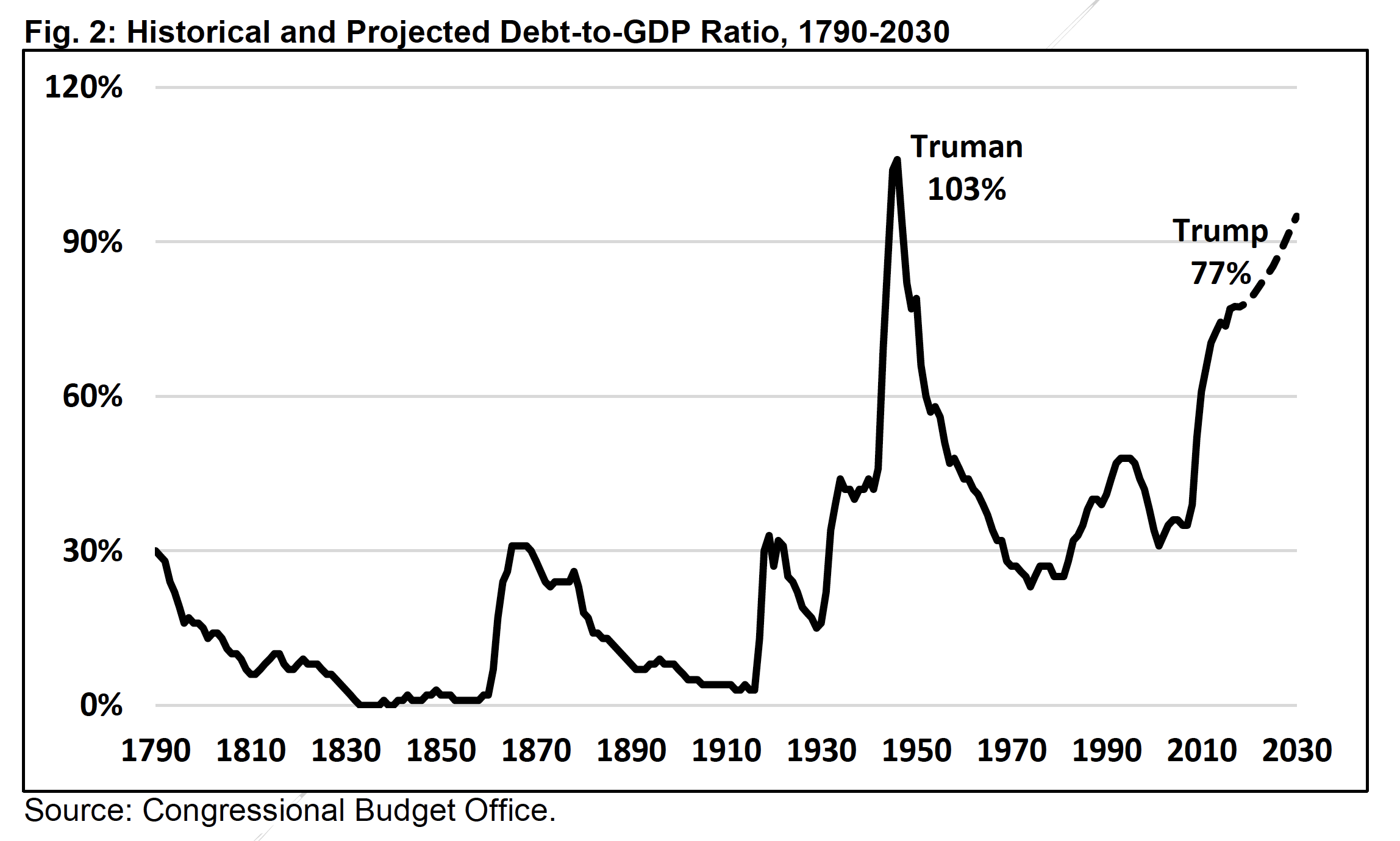

- President Trump has taken office with higher levels of debt as a share of the economy than any president other than Harry Truman in 1945.

- Unlike the debt under President Truman, which began to fall rapidly shortly after World War II ended, debt is projected to rise continuously during President Trump’s time in office and beyond.

- Federal entitlement programs and interest currently represent a larger share of the budget than under any previous president, leaving relatively less room for defense and non-defense discretionary spending.

- If in office for two terms, President Trump could face the insolvency of three major trust funds, and an additional one – the Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund – soon after.

- Much of the current agenda under discussion could add to the national debt. While the previous two presidents, George W. Bush and Barack Obama, both passed deficit-increasing legislation in their first months in office, they did so in very different circumstances that don’t apply today.

Debt is Higher Than at Any Time Since Truman

Over the past 50 years, the national debt held by the public has averaged about 40 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and was only 35 percent of GDP as recently as 2007. Since then, debt has grown dramatically, and is now higher than at any time since just after World War II.

Between 2007 and 2016, debt more than doubled as a share of GDP, from 35 percent to 77 percent.

This means that President Trump entered office with higher debt than any president since Truman in 1945, when debt was 103 percent of GDP.

At 77 percent of GDP, debt at the beginning of President Trump’s term is significantly higher than the 58 percent of GDP when President Eisenhower took office, the 46 percent when President Clinton entered, or the 44 percent at the beginning of President Obama’s tenure.

These record high levels of debt by themselves can be a problem for the U.S. government and economy. As we’ve written before, debt at today’s levels leaves little fiscal space to deal with a war, recession, or other emergency. Over time, it is also likely to put upward pressure on interest rates, crowd out productive investment, and slow income and wage growth.

If debt levels were falling as a share of GDP, many of these consequences could be avoided – particularly given today’s abnormally low interest rates. Unfortunately, and unlike after past spikes in the debt, debt levels are continuing to rise unsustainably.

Debt and Deficits Are Rising Unsustainably

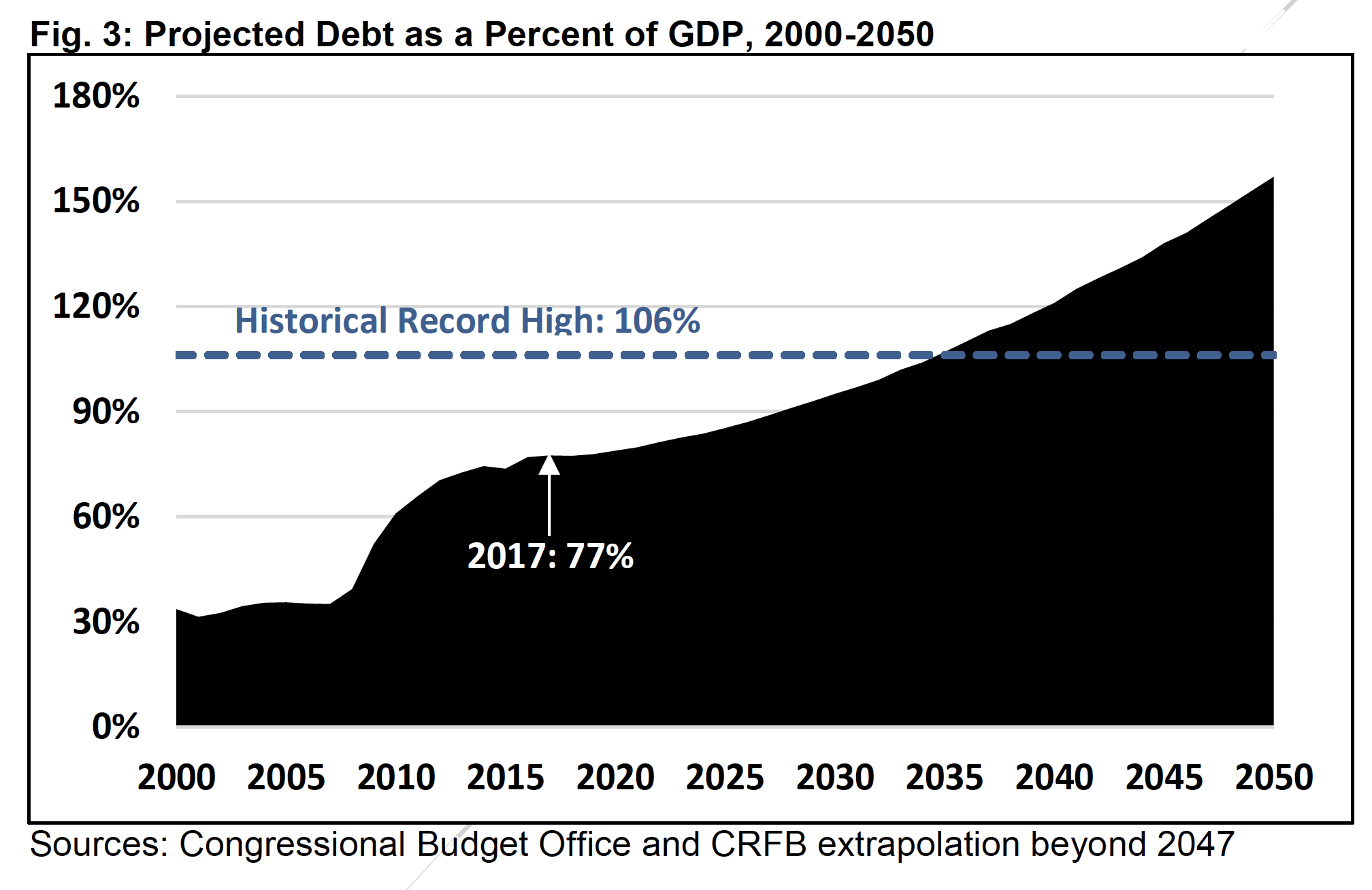

Though President Truman began his term with debt at 103 percent of GDP, he left office with debt reduced almost by half. The end of massive military expenditures to fight World War II, in combination with robust economic growth and several years of budget surpluses, allowed debt to fall from a peak of 106 percent of GDP in 1946 down to 58 percent of GDP when he left office in 1953.

By contrast, today’s debt is on an upward path. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that under current law debt will rise from 77 percent of GDP today to 89 percent of GDP by 2027, the highest level since 1947 and the fourth-highest year-end total in U.S. history. CBO further projects that debt will exceed its historical record of 106 percent of GDP by 2035, and will be on a path to exceed 150 percent of GDP before 2050.

Annual deficits are also rising rapidly. Deficits totaled $587 billion in 2016, and CBO projects trillion-dollar deficits will return by 2023. As a share of the economy, deficits are currently 3.1 percent of GDP and will reach 5.0 percent of GDP in 2027 and 9.0 percent of GDP within three decades – higher than any time except for 5 years during World War II and the Great Recession.

This trajectory is unsustainable. Debt cannot forever rise faster than the economy. CBO has explained that “Such high and rising debt would have serious negative consequences for the budget and the nation,” including slower economic growth, higher spending on interest payments, less flexibility to respond to emergencies and changing priorities, and an increased risk of a severe fiscal crisis.

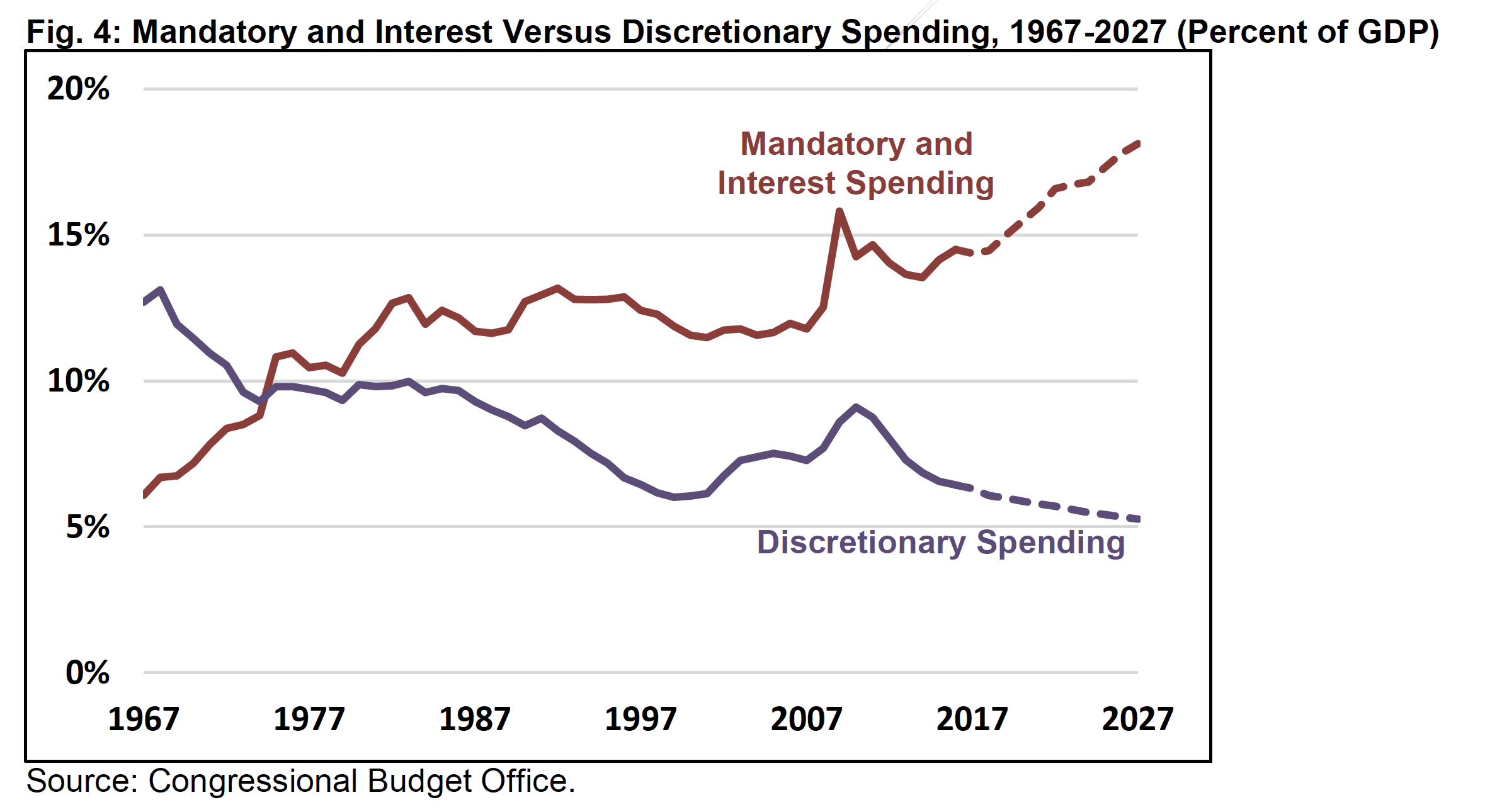

Mandatory Spending is Dominating the Budget

Not only does the country face high and rising deficits and debt, but the composition of government spending is undergoing a dramatic change. 50 years ago, two-thirds of government spending was “discretionary,” meaning lawmakers decided how to allocate it each year. 40 years ago, about half of government spending was discretionary. Today, only about one-third of government spending is discretionary, and by 2027, less than one-quarter will be. That means that over the next decade, on average, three-quarters of the budget will be on autopilot.

Over time, the passage, expansion, and rising cost of mandatory entitlement programs have caused them to dominate an increasing share of the federal budget. As the population ages and health care costs rise, the three largest entitlement programs – Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid – are projected to continue to rise dramatically in cost.

Indeed, Social Security and federal health spending are responsible for 63 percent of nominal spending growth and 93 percent of spending growth as a share of GDP over the next decade. Spending on interest on the debt, which is the fastest growing part of the budget, is responsible for another 19 percent of the spending growth and 49 percent as a share of the economy.

With mandatory spending and interest costs growing rapidly, there is little room for growth in the defense or non-defense discretionary budgets. As a share of GDP, they have already fallen by half, from 12.7 percent in 1967 to 6.3 percent today. And they are headed even lower, to 5.3 percent of GDP by 2027 – the lowest total on record (which goes back to 1962).

With a growing share of funds dedicated to past promises, a declining share is available for future investments in education, infrastructure, national defense, homeland security, and basic research.

Trust Funds Are Headed Toward Insolvency

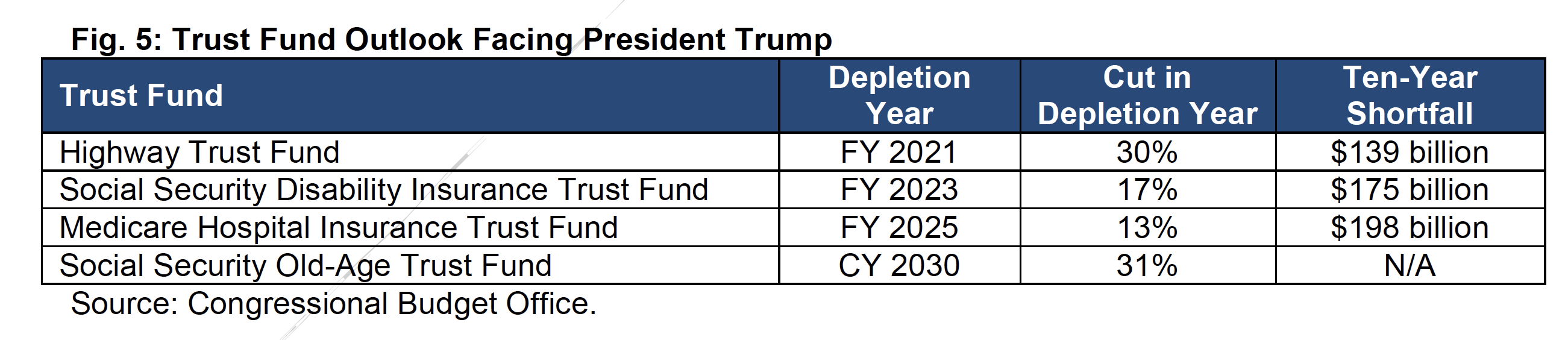

In addition to the overall debt and deficit situation, President Trump is confronted with a number of major trust funds out of long-term balance, with three that could be depleted by the end of a hypothetical second term in office.

CBO projects the Highway Trust Fund to become insolvent some time in Fiscal Year (FY) 2021. At that point, $70 billion of general revenue that was transferred into the trust fund in 2016 will have been spent in its entirety. As a result, the $40 billion of dedicated revenue will fall about one-third short of the projected $57 billion in spending in 2021. Through 2027, spending will exceed revenue and trust fund reserves by $139 billion, requiring significant adjustments to align them.

Two years later, in FY 2023, CBO projects the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) trust fund will exhaust its reserves. When that happens, beneficiaries will face an immediate 16 percent benefit cut. To delay this cut, policymakers will need to close a $175 billion shortfall between 2023 and 2027. Over a 75-year period, the SSDI shortfall equals 0.65 percent of taxable payroll (the Social Security Trustees estimate a 75-year shortfall of 0.26 percent of payroll).

By FY 2025 – either near the end of a hypothetical second term or the beginning of the following president’s term – CBO projects the Medicare Hospital Insurance trust fund, which funds Medicare Part A, will also reach insolvency. When this trust fund is depleted, Medicare payments would be cut by 13 percent unless policymakers close the program’s $198 billion shortfall between 2025 and 2027 and the significantly larger long-run deficit (the Medicare Trustees project Medicare will be insolvent by 2028 and faces a shortfall of 0.73 percent of taxable payroll.)

Finally, CBO projects Social Security’s Old-Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund will deplete its reserves by calendar year (CY) 2030. At that point, under current law, all beneficiaries would face a 31 percent benefit cut. Though this date is still 13 years away, it is unlikely policymakers will be able to prevent insolvency (or prevent a large general revenue transfer) if they don’t act in the next few years. As we’ve explained before, delaying action on Social Security will ultimately require larger tax increases and spending cuts spread over fewer cohorts with fewer possible exemptions (such as current beneficiaries) and less time for workers to plan and adjust. Over 75 years, CBO projects Social Security’s retirement program faces a massive gap of 4 percent of payroll – the equivalent of one quarter of spending or one third of revenue (the Social Security Trustees estimate a 75-year shortfall of 2.39 percent of payroll and an insolvency date of 2035).

In 2001 and 2009 We Added to the Debt, But This Time is Different

Much of the current agenda under discussion between President Trump and Congress is focused on reducing tax rates, expanding infrastructure, and increasing defense spending. If these agenda items are not fully offset, they could significantly add to the already-unsustainable national debt.

Adding to the debt early in a presidency would certainly not be unprecedented. The prior two presidents, Barack Obama and George W. Bush, both supported and signed into law significant deficit-increasing legislation within months of taking office. However, the fiscal and economic context that made deficit-financed legislation possible or even desirable in 2001 and 2009 does not apply today. This time is different.

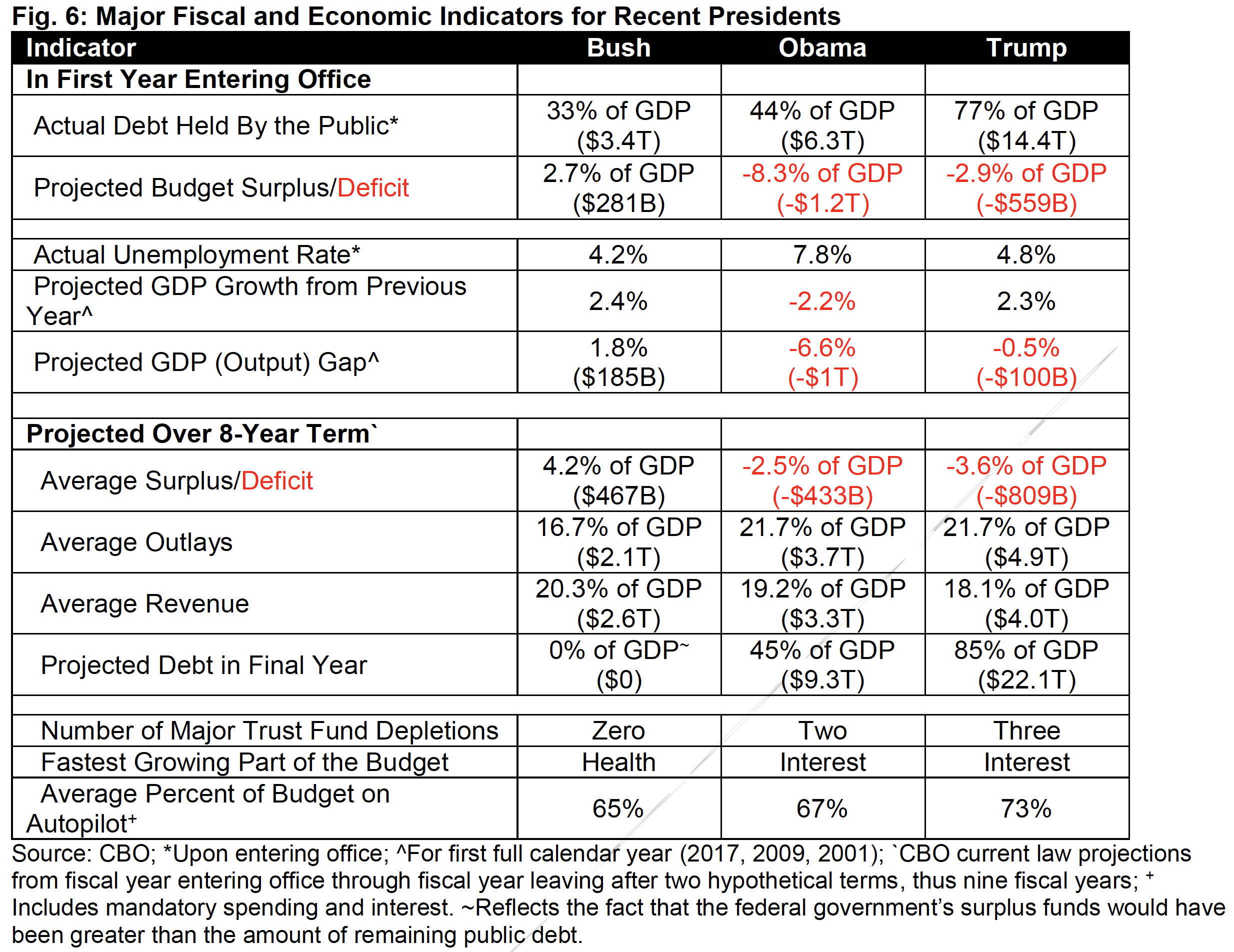

When President Bush took office, the budget was in surplus. CBO projected a $281 billion (2.7 percent of GDP) surplus in 2001 and average surpluses of $467 billion per year (4.2 percent of GDP) during the nine fiscal years he would be in office (the eight calendar years of his terms were part of nine fiscal years). Debt equaled 33 percent of GDP and was on course to be paid off. The tax cuts enacted at the beginning of President Bush’s presidency were justified by proponents as returning surpluses to taxpayers and were designed – at least in theory – to only consume a fraction of these surpluses.

Of course, the passage of significant additional tax cuts and spending increases, along with a weaker than projected economy, ultimately turned surpluses into deficits. We opposed the unpaid-for policy choices that lead to these deficits, but it is important to recognize that the justification for them was at least stronger with surpluses than with growing deficits.

President Obama didn’t inherit budget surpluses when he took office. But he did face the deepest economic downturn since the Great Depression, with an unemployment rate at 8 percent and rising and GDP levels estimated to be nearly 7 percent – or $1 trillion – below potential. At the time, economists of all stripes were arguing for a debt-financed injection of funds into the economy. With debt at 44 percent of GDP – suggesting substantial fiscal space – President Obama signed into law a roughly $800 billion stimulus package designed to help the economy recover.

Unlike President Bush, President Trump does not have large budgetary surpluses – deficits are projected to average more than $800 billion per year during the nine fiscal years he could potentially be in office. Unlike President Obama, President Trump does not face an economy deep in recession – the unemployment rate is 4.8 percent, and CBO estimates the economy is only 0.7 percent below potential. And unlike either, he did not enter office with a relatively harmless debt-to-GDP ratio – he enters with higher debt than any president besides President Truman.

While there was a case for passing debt-financed legislation at the beginning of the Bush and Obama administrations, no such case exists for Trump.

Conclusion

President Trump is beginning his presidency facing a challenging fiscal situation, with near record-high debt and deficits expected to rise substantially. This situation may help determine the agenda that he and Congress undertake over the next four years, either as a constraint on what they pass or a motivation to pass deficit reduction legislation.

The unprecedented fiscal challenges he faces should help motivate the administration and Congress to fully pay for all new legislation and work together to pass a plan to control the debt and put it on a downward path.

We hope that the new president and Congress will use this opportunity to improve our fiscal situation and restore fiscal sustainability. Doing so is critical to securing both our fiscal and economic futures, and it will help restore the resources and flexibility needed to address other critical priorities.

What's Next

-

Image

-

-

Image