Sovereign Risk Jitters

For budget and market watchers, the month of March has been a little scary. It is not easy to come out of the deepest recession and financial crisis since the 1930s, particularly when the fiscal outlook and prospects for its successful management are so uncertain.

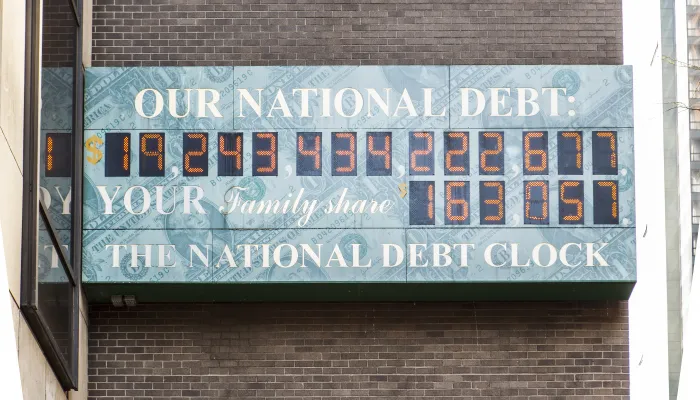

Sovereign risk jitters are on the rise as markets are being asked to digest massive amounts of government debt, at the same time the supply of private sector debt going to market is increasing and investors' appetite for risk is returning. The changes underway are complex and shifts could well be sudden.

In Europe, sovereign debt crises are unfolding in Greece and now Portugal (whose sovereign debt was just downgraded by Fitch, a leading credit ratings agency). If not managed well, the credibility of the euro and perhaps even the foundation of the European Union may be at risk. The United Kingdom has just produced its new budget. And, as noted economist Martin Wolff commented, when a deficit of nearly 12 percent of GDP expected this year is considered good news, we are indeed in trouble.

Here in the United States, we have started to see problems at our Treasury auctions, which may be harbingers of a shift in investor preferences and expectations:

- In February and more recently, markets reportedly demanded a greater risk premium for the purchase of Treasury debt than for comparable corporate debt. In February, the yield on two year Treasury notes was higher than the yield on comparable debt instruments for Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway company and the debt securities of a few other blue chip companies. This may be the first time (at least in recent memory) that a private debt instrument was considered less risky than a government debt instrument.

- On March 23 and 24, U.S. interest rate swap spreads were the smallest in 20 years. For for some maturities, spreads were even negative. In the ten year market, the change was referred to as the "historic inversion". (Considered an early warning sign of market risk, the spread is the difference between the rate to exchange floating for fixed interest rate-based payments and the yield on comparable Treasury instruments.)

- Moody's recently announced that while the U.S. would retain its Aaa rating now, it might be at risk at some point in the near future unless it adopted a credible medium-run fiscal consolidation plan. Moody's has also noted that, along with the U.K., the U.S. has the highest debt service as a share of revenue (considered a key measure of debt affordability) among the major industrial countries.

We can also see sovereign jitters in recent statements by our major creditors. Chinese government leaders have expressed concerns over U.S. fiscal management and worry that we might attempt to manage our debt through an increase in inflation, which would hurt their holdings. Today, Bill Gross, head of the world's largest bond fund (PIMCO or the Pacific Investment Management Company, typically referred to as the leading "bond vigilante" group), advised investors to shift from high debtor countries like the U.S., U.K. and Japan to lower borrowing countries like Canada and Germany, increase investments in private debt, and go for shorter maturities. His worries reflect the view that real interest rates are heading up as the economy picks up and the Fed tightens to head off higher inflation. Many leading experts, in contrast, see the risk of inflation and Fed tightening to come later.

Sovereign risk worries were undoubtedly heightened by recent remarks made by International Monetary Fund Deputy Managing Director John Lipsky, who noted that most of the G-7 countries will have debt close to or above 100 percent by 2014. The exceptions he noted were Canada and Germany, both of which are in relatively stronger fiscal positions. (PIMCO's Bill Gross had also positively singled out these two countries. Click here for details on Canada's fiscal turnaround.)

For the U.S., all of this is likely a harbinger of things to come. As our economy continues to recover, investors may not seek dollar-denominated investments, including Treasury debt, as safe havens. Preferring yield in the absence of another crisis, our creditors will be less willing to accept low returns on US debt and will shift assets out of dollars. They may also show a greater preference for sovereign debt at the shorter end of the market, to minimize risk. Fears of inflation to manage our debt burden will also be increasingly reflected in investor pricing and purchase of our debt. Higher interest rates will crowd out investment, which will hurt underlying growth and ultimately our standards of living.

It is important that our policymakers understand that the rise in sovereign risk jitters significantly reflects a rise in political risk perceived by the markets. It is all too apparent that we do not have an exit strategy to unwind the massive debt accumulated to address the crisis. Added to the picture, the fiscal challenges posed by an aging population are expected to start kicking in within the next 5-10 years. It is no surprise that our creditors see debt rising as far as the eye can see - and with no end in sight.

In the United States, market perception of political gridlock is undermining the fiscal management credibility of the government. Going forward, we will not be able to manage creditor expectations unless we come up with a strategic view and plan of how to manage our challenges. Otherwise, we should look forward to persistent debt finance problems (perhaps even crises) in the years to come. We should take heed from an important paper in which the authors (Robert Rubin, Peter Orszag and Allan Sinai in 2004) argued that because investors are forward-looking and adjust quickly, fundamental expectations may shift - and shift abruptly - when large budget deficits are projected well into the future.

Unless our political leaders eliminate the uncertainty of our fiscal future through the adoption of a fiscal recovery plan that can be implemented gradually but steadily, the full faith and credit of the United States may well be increasingly seen at risk. Our policymakers are in a position to do something about it sooner rather than later, in the national interest.