Social Security Should Be Part of the Conversation

All eyes are on the budget conference committee, which has a myriad of options available to consider as it negotiates this year's budget resolution. Some advocates and lawmakers have been discussing Social Security reform as an area that might be able to get bipartisan consensus. While the budget conference committee cannot address Social Security due to procedural rules, a separate process to fix Social Security would not only make that program solvent, it would also improve the long-term budget picture.

In our recent paper, What We Hope To See From the Budget Conference Committee, we called on the conference committee to recommend fixing Social Security on a separate track. Although the program is funded by its own stream of revenues, Social Security's costs are increasing as the population ages, from 4 percent of GDP in 2006 to nearly 5 percent today, and will reach 6 percent of GDP before 2030. In fact, the program began running a cash-flow deficit in 2010, which will continue indefinitely and will require the federal government to borrow more going forward to make up the difference.

As a result of the imbalance between revenues and spending, the trust fund for the disability program is projected to run out of reserves in 2016 and the retirement program in the 2030s. If the programs are reformed soon, changes can be much more gradual than if Congress waits 20 years to address the shortfall.

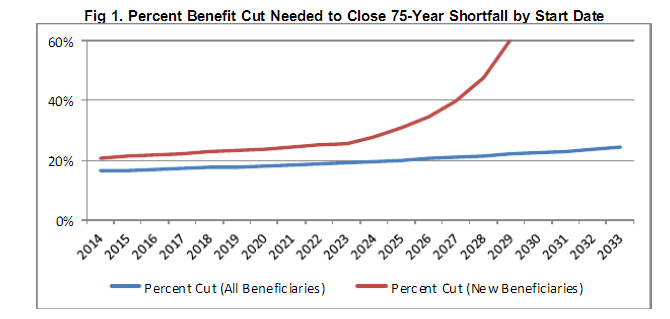

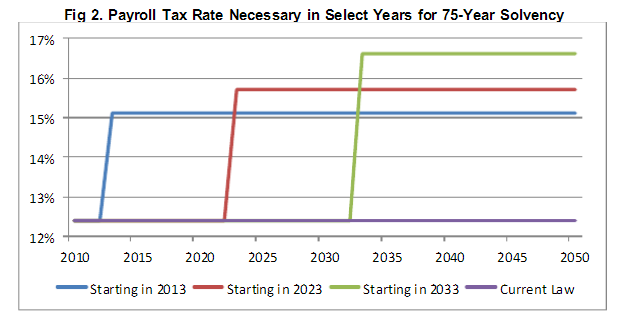

According to our recent paper on the cost of delay, waiting until the program is almost insolvent will require much larger benefit cuts. In a hypothetical example shown below, closing the program's funding gap with only benefit cuts would require a cut of nearly 20 percent this year, 30 percent in a decade, and 83 percent by 2030. Restoring program solvency solely by raising taxes tells a similar story: the costs of waiting grow ever greater. An immediate increase in the payroll tax from 12.4 percent to 15.1 percent would achieve 75-year solvency. If taxes were not raised until 2023, the necessary rate would be 15.7 percent. If we waited until 2033, the necessary rate would be 16.6 percent.

Regardless whether you look at Social Security as a stand alone program or as part of the federal budget, the data unmistakably points to the need for reform. When viewed as its own program, Social Security faces abrupt spending cuts once it exhausts its assets in the 2030s — clearly a bad scenario for beneficiaries. As part of the federal budget, however, even though Social Security has dedicated trust funds and is technically "off-budget," it still pays out more annually than it takes in. Regardless of whether past surpluses were saved in an economic sense or not, the federal government will have to borrow more to make up for its cash flow deficit. If Social Security were brought into balance, the unified deficit would be 20 percent smaller by 2035.

Many think that Social Security reform might actually be easier to tackle, because the demographic trends are clear and there is a fairly short list of options that could fix the problem, which must either increase future revenue into the trust funds or decrease future benefits paid out. We've put together the most common options in the Social Security Reformer, a tool which lets you create your own plan to fix Social Security.

So what can the conference committee do?

In reality, any successful Social Security reform package will contain a mix of benefit cuts and increased revenues. Although the numbers in the budget resolution do not include revenues and outlays for the Social Security trusts funds and the conference committee is not allowed to include any changes to Social Security or issue reconciliation instructions that affect the program, it could make non-binding assumptions about changes to Social Security or call for a process for future Social Security reform separate from deficit reduction.

For instance, the budget conference committee could call for adopting the chained CPI with low-income protections, which includes approximately $230 billion in savings from all parts of government, with the $145 billion in on-budget savings incorporated into the budget resolution totals and a non-binding recommendation that the policy be applied to Social Security as well. The budget conference could include a non-binding policy statement reflecting an agreement to use the Social Security savings from the chained CPI, along with another proposal with some bipartisan support like gradually raising the maximum wages subject to the payroll tax back to its historic norm, as a down payment towards Social Security reform. According to our Social Security Reformer, these two policies together would address nearly half of Social Security's 75-year shortfall. A future Commission tasked with making Social Security solvent would already be halfway to the goal.

The budget could also include a non-binding policy statement calling for a process to restore Social Security solvency, such as a trigger requiring proposals to be submitted to restore solvency with a fast track process for legislative action, a reform commission, or a deadline for Committee markup of a Social Security reform bill. The House-passed budget resolution included such a policy statement: recommending a trigger requiring the Social Security Trustees to submit a plan to restore solvency and requiring Congress to vote on the Trustees' recommendations or an alternative package to achieve solvency.

The conference committee's primary focus should be achievable savings that improve the nation's long-term fiscal situation. The conference committee cannot directly address Social Security, but the committee should not miss the opportunity to establish a process for future Social Security reforms, which will have the side effect of contributing to deficit reduction.

To read our other recommendations to the budget conference committee, click here.

Click for our Social Security Reformer, a tool to show how to make Social Security solvent over the next 10 years.