One Simple Way to Undermine Fiscal Credibility

A new report from the Center for American Progress argues that roughly 60 percent of the sequester should be waived in light of the savings from the fiscal cliff deal in January, which allowed taxes to rise on the top 1 percent or so of Americans.

CAP argues that the $737 billion in savings (relative to a current policy baseline) from the fiscal cliff package were not applied to the sequester but should have been. They suggest retroactively using this savings to reduce the future savings from sequester from $1.2 trillion (including interest) to $463 billion.

As we’ve explained before, a plan like this would represent a serious step backward for responsible budgeting. Not only would the CAP plan increase deficits by almost $750 billion over the next decade compared to current law, but it would undermine the country’s fiscal credibility by violating pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) principles, which say that policymakers must fully pay for any new tax cuts or spending increases, and proving that policymakers cannot stand by agreed-upon deficit reduction. Waiving those cuts without any replacement savings would increase current law debt projections by roughly three percentage points a decade from now, though keeping part of the sequester would reduce the debt slightly compared to the CRFB Realistic Baseline.

In addition to these broader concerns, CAP’s argument for applying $737 billion against the sequester makes little sense. Below, we walk through a number of reasons why.

The Fiscal Cliff Deal Didn’t Reduce Current Law Deficits, It Increased Them

The Center for American Progress claims that the fiscal cliff deal produced substantial deficits reduction that could have been applied to reduce the sequester. Yet, compared to a current law baseline, the fiscal cliff deal did not reduce the deficit by raising taxes, it increased the deficit by renewing tax cuts and spending increases slated to expire. At the time, CBO estimated the deal would add nearly $4 trillion to deficits through 2022, excluding interest effects.

It’s true that the deal did raise revenue relative to a current policy baseline, like CRFB’s Realistic Baseline. But pay-as-you-go rules do not and should not apply relative to current policy. The idea of PAYGO is to prevent an unsustainable current law fiscal situation from being made worse. As we explained at the time, policymakers should not have renewed the tax cuts and waived the sequester outside of PAYGO rules unless they were replacing the provisions with a plan to put the debt on a sustainable long-term path.

As we explained in July 2012:

Gradually phasing in well thought-out entitlement and tax changes would be far preferable to large, blunt, and abrupt savings upfront…However, the worst case scenario would be for lawmakers to repeal the sequester and once again extend expiring debt-expanding policies without offsetting their costs.

The fiscal cliff deal, although it included some savings relative to current policy, violated this principle by adding to the deficit and leaving an unsustainable fiscal path. Further increasing the deficit and worsening the fiscal outlook would be a huge step in the wrong direction.

There Has Only Been About $325 $275 Billion of Deficit Reduction from Current Policy, Not $737 Billion

The idea that the fiscal cliff deal could cover 60 percent of the sequester is based on fuzzy math that compares $737 billion of gross savings through 2022 to a $1.2 trillion savings target through 2021.[1]

Those savings are apples to oranges in a number of ways. Correcting the fiscal cliff time frame to be through 2021, for starters, reduces the savings from the fiscal cliff from $737 billion to about $615 billion.

The savings number CAP quotes also includes about $20 billion through 2021 that, though deficit reduction relative to current policy, was clearly earmarked for a “doc fix”. But we still give CAP credit for this relative to most current policy baselines. $40 billion (through 2021) that was earmarked at the time to pay for a “doc fix” and sequester extension. It also excludes the roughly $75 billion cost of extending various business tax cuts. When these factors are taken into account, including interest effects too, total “savings” from the fiscal cliff deal are not $737 billion, but rather $525 $475 billion.

On top of this, the CAP numbers cherry pick the supposed savings from the fiscal cliff deal but ignore other legislation since August 2011 that has added to the deficit. Including interest, we’ve added over $200 billion to the deficit (through 2021) between the extension of the payroll tax holiday, the hidden discretionary spending increases from higher federal retirement contributions, and relief for Hurricane Sandy.[2]

If one accounted for all major deficit-changing measures since the Super Committee and counted the savings relative to the CRFB Realistic Baseline, the total savings would be closer to $325 $275 billion, not $737 billion.

| Ten-Year Savings and Costs (Including Interest) | |

| Claimed Fiscal Cliff Savings Through 2022 | $737 billion |

| Adjustment from 2013-2022 window to the sequester’s 2012-2021 window | -$125 billion |

| Incorporated costs of fiscal cliff extenders package | -$90 billion |

| Subtotal, Fiscal Cliff Savings (2012-2021) | $525 billion |

| Costs of other notable legislation since late 2011 (payroll tax extensions, Sandy aid, etc.) | -$200 billion |

| Total, Net Budgetary Impact |

~$325 billion |

Note: Estimates are rounded to the nearest $5 billion.

Enacted “Deficit Reduction” Plus Sequester Savings Still Fall Short of Super Committee Target

CAP claims that the $737 billion in "savings" from the fiscal cliff deal would justify a 60 percent reduction in the sequester. Yet, with only $325 $275 billion of deficit reduction actually enacted since the Super Committee relative to a current policy baseline with the sequester (and massive deficit increases from current law), the most that could be justified is a 1/3 32 percent reduction in the total sequester through 2021 and a 35 percent reduction going forward (the sequester would have saved about $1 trillion through 2021, including about $925 billion from the 2014-2021 sequester). But applying any of these savings to sequester relief would ensure far fewer savings than the original Super Committee was charged with recommending.

As CRFB has explained before, the Super Committee was charged with identifying $1.5 trillion of deficit reduction through 2021. For a variety of reasons, however, the sequester is now expected to generate just above $1 trillion of deficit reduction over that time period. Even crediting the supposed enacted deficit reduction of about $325 $275 billion to that total would still result in only $1.3 trillion, still short of the Super Committee target by a little over 11 13 percent (and only 11 8 percent in excess of the original sequester target). If we exclude the cost of deficit-increasing legislation over the past two years, the total would just about meet the original Super Committee target.

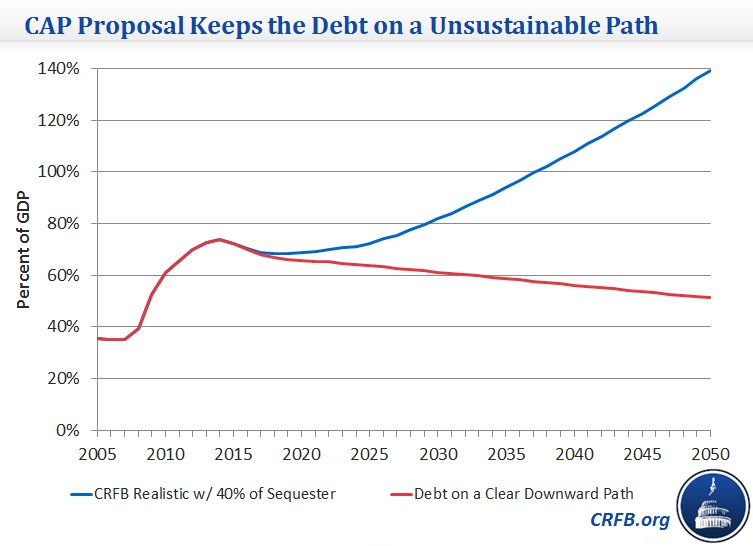

CAP Proposal Would Worsen the Unsustainable Fiscal Picture

The main purpose of pay-as-you-go principles is to keep Congress from worsening the already-bleak fiscal situation. Instead, the CAP proposal adds nearly $750 billion to the deficit over the next decadeand allows the debt to grow continuously as a share of GDP (though if the remaining sequester from the proposal remained in place, debt could be more than $400 billion lower through 2023 than under the CRFB Realistic Baseline).

It’s true that under the proposal debt levels will decline between 2014 and 2018 – just as under current policy. But under our projections, the debt would still rise from 68 percent of GDP in 2018 to 71 percent if 2023, 94 percent in 2035, and nearly 140 percent by 2050.

CAP Proposal Would Undermine Fiscal Credibility

Replacing the sequester with more sensible and permanent deficit reduction would likely improve the economy and long-term fiscal situation. But repealing parts of the sequester on a deficit-financed basis would undermine fiscal credibility at a time when it is needed most.

First, as mentioned before, it violates pay-as-you-go principles. This violation would be especially egregious since it would be justified using so-called revenue that came from violating PAYGO principles and a much more lenient statutory PAYGO law.

Even more troubling, waiving the sequester would demonstrate that policymakers cannot stick to agreed-upon deficit reduction. Sequestration was explicitly put forward, on a bipartisan basis, as an enforcement mechanism to ensure policymakers identified at least $1.2 trillion (with a target of at least $1.5 trillion) of deficit reduction through 2021. That the Super Committee and subsequent fiscal cliff negotiations failed to result in this deficit reduction is bad enough, but cancelling the enforcement could undermine the credibility of all future deficit reduction promises. With debt at twice its historic average and the highest it has been since World War II, faith that the U.S. will make good on its debt promises is as important as ever.

* * * * *

There is no question that the sequester is the wrong way to reduce the deficit – it is mindless, anti-growth, poorly targeted, and does very little to improve the long-term fiscal picture. But these flaws suggest the sequester should be replaced with more permanent, better targeted, longer-term savings, not waived altogether. As the chairman of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers Jason Furman has said recently, replacing the sequester with smarter savings is not only good politics but sensible economic policy as well.

Conversely, reducing the sequester cuts without paying for them is not only politically unpalatable but poor economic policy as well. The plan to deficit-finance a 60 percent reduction in sequester cuts is based on selective math, has no real justification, adds roughly three percentage points to the debt by the end of the decade, and undermines the country’s fiscal credibility.

Just because you get closer to the finish line doesn’t mean you lay off the gas, and it certainly doesn’t justify putting the car in reverse. Lawmakers should pursue long-term deficit reduction measures because we still face unsustainable levels of debt and the sooner we act the easier it will be.

[1] Coincidentally, the actual cost of repealing the sequester through 2023 will also be about $1.2 trillion, including extrapolated discretionary costs – smaller than originally intended.

[2] The payroll tax holiday and discretionary retirement adjustments would likely have been incorporated as costs had the Super Committee reached agreement.

Note: This blog has been updated since original posting based on new information provided to us from CAP on the elements of their $737 billion estimate. All additions have been made in green and deletions changes have been marked with strikethroughs.