Moore v. US Ruling Could Widen Deficits, Upend Tax Law

A pending Supreme Court case, Moore v. United States, could have implications that undermine existing tax law, upend the tax code, and cost the U.S. billions in lost revenue over the decade. The Court’s decision could end up costing the federal government anywhere from $3 billion to $1 trillion of lost revenue over the decade, while creating huge loopholes in the tax code.

The case questions the constitutionality of a transition tax implemented under the Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA), on deemed repatriation of certain income held abroad. The Moores, in particular, own shares in a controlled foreign corporation and following the TCJA claim to have received a tax bill for their profit shares despite never receiving any dividends or capital gains. The plaintiffs argue that this is a tax on property and further argue that this constitutes a form of “direct tax” in violation of the 16th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

Experts in tax law and tax policy are virtually unified in their support of the legality and logic of the TCJA's mandatory repatriation tax (MRT). Numerous amici briefs have been filed in support of the government’s position warning that continued litigation, abusive tax strategies, distortion of income, and widespread effects on federal revenue could follow a ruling in favor of the Moores. This includes many briefs from those on the right side of the political spectrum who generally support lower taxes.

But separate from any legal questions, a Court ruling in favor of the Moores could prove very costly to the federal Treasury, as highlighted in a recent analysis from the Tax Foundation.

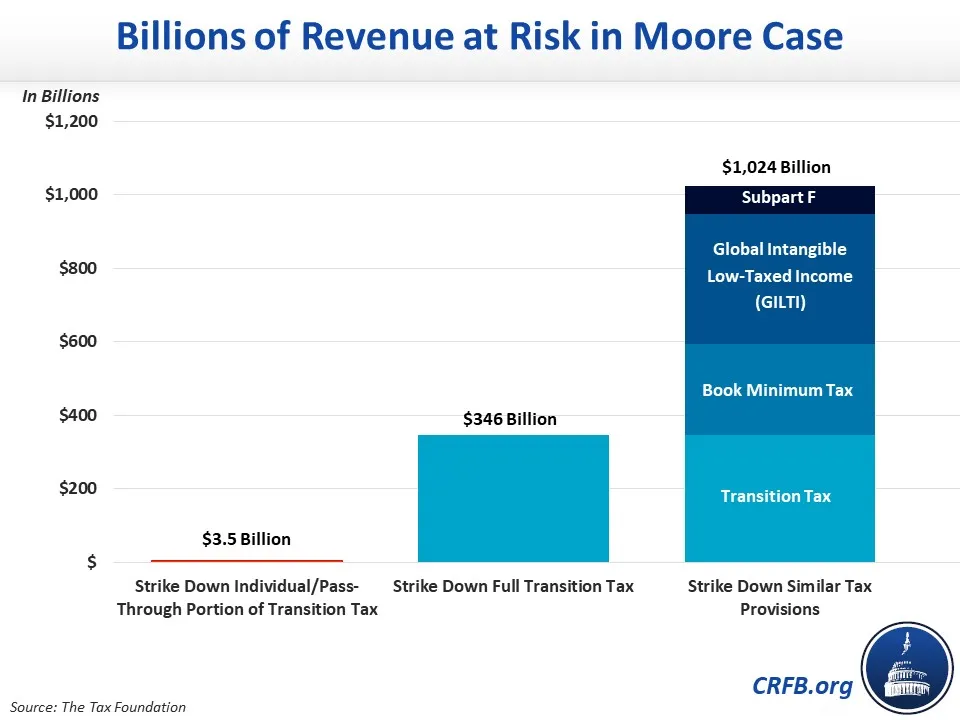

A very narrow ruling in favor of the Moores, which essentially strikes down the transition tax for pass-through firms and individuals only, would cost about $3.5 billion, as much as funding the Drug Enforcement Administration for an entire year. A broader ruling could ultimately strike down the entire transition tax, costing $346 billion, which is about what the government is projected to raise from gas and diesel taxes or spend on school breakfasts and lunches. Such a ruling would also allow a large amount of corporate income to permanently evade taxation and undermine the international tax reforms made under the TCJA.

If the court rules the transition tax is a form of direct tax, that logic might also apply to other provisions that rely to some degree on taxing earnings that haven’t been fully realized, repatriated, and distributed. For example, Subpart F – which prevents certain U.S. taxpayers from shifting passive income to foreign subsidiary companies in order to avoid taxes – taxes income even if it technically remains abroad. The global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) tax in a similar fashion discourages companies from shifting intangible assets like intellectual property abroad for tax purposes. And the new 15 percent book minimum tax from the Inflation Reduction Act is imposed on a measure of financial income that counts various sources of technically unrealized income.

If all three corporate tax provisions were struck down along with the transition tax, it would reduce revenue by over $1 trillion.

The potential $1 trillion cost of a broad Moore v. U.S. ruling is equivalent to:

- The 10-year cost of all premium subsidies under the Affordable Care Act

- All revenue collected from excise taxes over the next decade

- The vast majority of the savings generated from the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023

- The 10-year cost of increasing the Child Tax Credit (CTC) by $1,500 per year

- The 10-year cost of reducing the corporate tax rate from 21 to about 14 percent

And as analysts at the Tax Policy Center have pointed out, an even broader set of tax provisions could also be on the chopping block. As would new provisions designed to comply with Pillar II of the OECD’s global anti-base erosion rules.

The Tax Foundation estimates $5.7 trillion of revenue losses from an extremely broad interpretation, where the court strikes down taxes on all undistributed business earnings. Such a ruling would fully undermine business taxes by ending all taxation of retained corporate and pass-through earnings.

While the above interpretation is extreme and unlikely, even a narrow interpretation might inhibit Congress’s ability to improve the tax code or raise more revenue in the future. It may also lead to years of uncertainty and litigation to further clarify the tax code.

With revenue below the historic average and debt approaching record levels, now is not the time to be weakening the revenue base. A ruling in favor of the Moores would not only undermine reforms from the TCJA, but could also prove very costly.