Jared Bernstein Agrees -- There is No Free Lunch

Nearly a month ago, we tried to dispel the claim that due to low interest rates, borrowing was essentially a free lunch. As we explained at the time, borrowing today could add permanently to the debt stock, and with average debt maturity at about four years, most debt will be rolled over into higher interest rates relatively quickly. A couple weeks ago, we further discussed the possibility of interest rates rising, pointing to an excellent piece by economist Ken Rogoff.

Yesterday, on his blog, Jared Bernstein added to the discussion of whether such a "free lunch" exists. His conclusion: it doesn't, but perhaps we could have a cheap snack. As Bernstein explains:

[T]he government should be taking advantage of low borrowing rates but the advantage may be less than many who write about this think it is. The reason is because the government doesn’t pay off such debts after a year or two. It rolls them over and thus, under the plausible assumption that interest rates go up in the future, it pays that debt off at higher rates down the road.

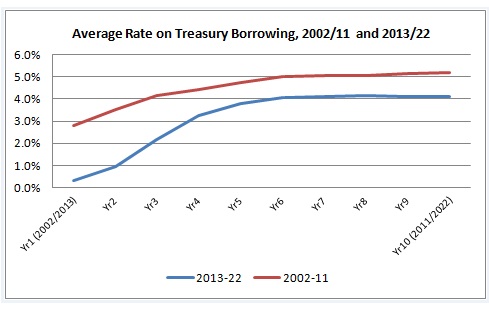

To show this, Bernstein conducts a thought experiment. He compares projected interest rates in 2002 to projected interest rates today and then calculates the interest cost of $300 billion in upfront borrowing.

Given the lower interest rates projected today by OMB -- Bernstein finds interest costs on $300 billion of stimulus would be roughly $100 billion over the next decade, compared with $150 billion over the ten years following 2002. "So, the savings from taking advantage of today’s low rates," he writes, "would be $50 billion. That’s by no means chump change, but it ain’t a free lunch either."

Indeed, even those numbers may overstate the actual savings for a couple of reasons. First of all, inflation projections are lower now than they were in 2002. Back then, OMB projected roughly 2.5 percent inflation per year; now they project closer to 2 percent. If we adjusted the interest costs for inflation projections, we should see a narrowing of the differences. Secondly, looking only at the ten-year time period will result in a larger proportional difference than taking a long-term view -- since more bonds will roll over as time goes on.

None of this is to say that there aren't arguments for the government spending now on what it intended to do anyway. But any claim of a free lunch is highly misleading.