By Maya MacGuineas

Last night I attended a curtain raiser dinner for today’s Dealing with America’s Debt Overhang event, hosted by New America Foundation’s Economic Growth Program. (If you can’t attend in person be sure to watch it online.)

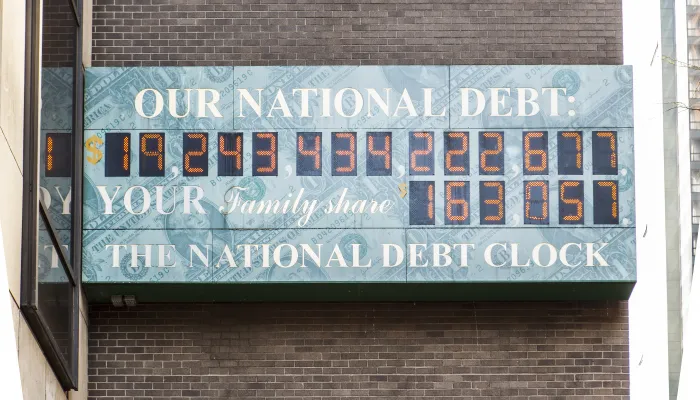

As a budget scold – as one of my dinner companions has called our ilk – who worries about medium-term deficits, I certainly held the minority viewpoint in the room that deficits do indeed matter. I share my colleagues’ concerns that the growth model of the past – where growth was driven by US consumption – will not be the model of the future, nor should it be. The US consumer de-leveraging process is likely to go on for some time. The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco has a study on U.S. Household Deleveraging and Future Consumption Growth showing that if the household saving rate were to rise from 4% to 10% by the end of 2018 (a reasonable scenario they predict) it would reduce annual consumption growth by ¾ ths of a percentage point each year.

Many at last night’s dinner argued that we should look to the US federal government to deficit finance government spending on public investments to fill the gap. There are, I believe, two arguments here: we need to find a new engine of growth, and the US government is not investing enough. I agree with both but differ from my colleagues on the solutions.

What will drive growth? I am not alone in my belief that we should look abroad to surplus countries such as China to consume more. Unfortunately, there is little we can do to force that, and the fact that much of the Chinese stimulus has focused on export related investments is not overly encouraging, though moves to shore up health insurance and pensions are likely to prove helpful.

But the risks of prolonged government deficit financing are too great. While the additional spending could help fill the output gap, there is no guarantee that there will be sufficient demand for the mammoth amount of borrowing that would require. Rumblings and grumblings from foreign government indicate they would like to have a better sense of how we are going to get our budget under control if they are to keep financing our deficits. Without a plan to bring down borrowing, interest rates at some point will be pushed up, potentially choking off a recovery. Sooner or later, a fiscal crisis would become inevitable. We don't know exactly when, but I would rather not find out. The real challenge then is evaluating the tension between helping to stimulate growth and avoiding a fiscal crisis. The risk aversion to a fiscal crisis is prudent because once you have gone too far, it is extremely difficult and painful to climb out of that hole.

Separately, I would agree that the government needs to spend more on public investments than it does (and do it better) – on everything from education to infrastructure to basic R&D. However, given how much we have borrowed in the past, there is little room for deficit financing new investments and I would instead shift our budget by cutting spending on consumption and directing it toward higher levels of public investment. If we had listened to budget scolds in the past, we would have more room on our balance sheet now for government borrowing - unfortunately, we did not.

Maya MacGuineas is the President of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.