The Benefits of Medicare Benefit Redesign

In a little over one month, lawmakers will face their second significant Fiscal Speed Bump of the year when the one-year "doc fix" expires. At that point, Medicare physician payments will be cut by 21 percent because of the long-standing Sustainable Growth Rate (SGR) formula. Policymakers have avoided the cuts since 2003 through temporary doc fix patches, but the relatively low cost of a permanent fix and a bipartisan, bicameral framework for replacement in the last Congress have increased the prospects that a permanent doc fix could finally happen.

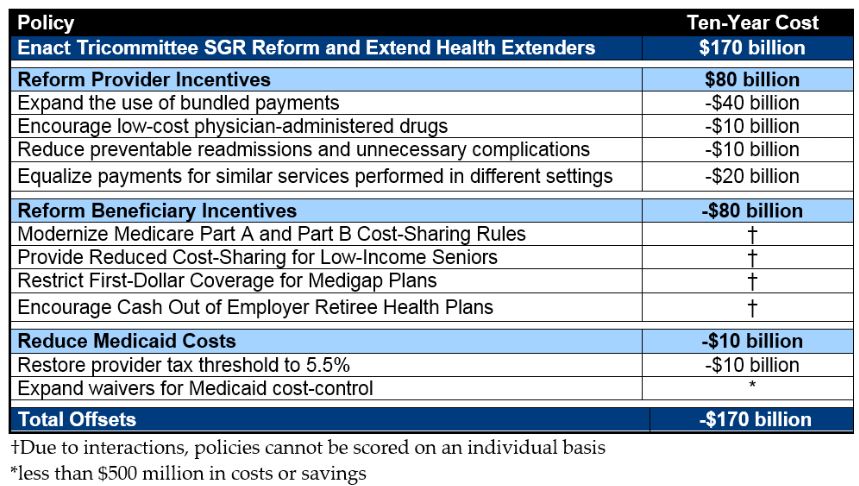

In the run-up to the lame duck session last Congress, we released the PREP Plan, which outlined tax and health savings options to pay for a two-year tax extenders and permanent doc fix package. Ultimately, lawmakers added the cost of one year of tax extenders to the debt, but they have the chance to keep with precedent and pay for a Medicare physician solution. The PREP plan divides savings equally between beneficiary and provider changes, focusing on reforms that can improve incentives.

The beneficiary changes in our plan would modernize Medicare's cost-sharing system by simplifying Part A and B deductibles and coinsurance, while creating a new out-of-pocket limit on cost-sharing. At the same time, the plan would restrict first-dollar coverage by supplemental insurance like Medigap to discourage over-utilization of care, and provide additional assistance to lower-income beneficiaries who need it most. Similar reforms have been proposed by Simpson-Bowles, the Bipartisan Policy Center, the Brookings Institution, and the Center for American Progress, among others.

Current Problems with the Medicare Benefit Design

Today, beneficiary cost-sharing responsibility in Medicare is uneven and bears little relation to the value of the service provided. Patients are responsible for a large deductible for each hospital inpatient admission – $1,260 in 2015 – which can quickly cause financial hardship. The lack of a cap on out-of-pocket expenses – arguably the core function of insurance – is almost unheard of in private insurance, and is in fact outlawed for Affordable Care Act (ACA) and Medicare Advantage (MA) health plans. This nearly necessitates that Medicare beneficiaries obtain supplemental coverage (90 percent do), which in turn provides a subsidy to private insurers selling expensive Medigap plans and unnecessarily drives up Medicare costs by entirely detaching patients from the cost of their health care.

Multiple studies have shown that beneficiaries with supplemental coverage use significantly more Medicare services without necessarily achieving better outcomes.1,2 By leaving many preventative services free of charge and exempting physician visits from the deductible, the proposed redesign should also minimize any reduced use of higher-value services.

According to a 2009 study commissioned by MedPAC, “total Medicare spending was 33 percent higher for beneficiaries with Medigap policies than for those with no supplemental coverage after controlling for demographics, income, education, and health status. Beneficiaries with employer-sponsored [supplemental] coverage had 17 percent higher Medicare spending, and those with both types of secondary coverage had 25 percent higher spending.”3

Medigap plans are also very expensive for their enrollees – the most popular Plan F costs more than $2,000 per year for first-dollar Medicare cost-sharing coverage, while each plan is only required to maintain a medical loss ratio of 65 percent, compared to the 80 percent required in the under-65 individual insurance market (that is, a plan only must spend 65 percent of enrollee’s premiums on health care coverage).4,5 Inadequate competition, with just two insurers controlling three-quarters of the Medigap market, likely adds to high Medigap premium costs.6 Currently, however, Medicare beneficiaries without Medicaid or employer-provided supplemental coverage have few options to protect themselves from the risks of extraordinarily high costs and potential medical bankruptcy – to do so, they must purchase a Medigap plan or enroll in Medicare Advantage.

How to Improve Medicare's Benefit Design

Reforming the benefit design, as outlined below, would provide Medicare beneficiaries with more sensible health care coverage of roughly the same actuarial value. Therefore, the plan would lower patient out-of-pocket costs on average because it would encourage more appropriate utilization of care, through a cap on annual out-of-pocket liability, a higher deductible for many non-hospital services, and by adding cost-sharing to certain services that currently have none (which may also help reduce fraudulent provider behavior in those fields).

The reform would maintain annual wellness visits (including the Welcome to Medicare physical) and certain preventative services -- such as flu shots, diabetes screenings, and certain cancer screenings -- free of charge. Additionally, physician visits would be exempt from the deductible, therefore requiring only a coinsurance payment for such services even before the new combined deductible is met.

| Parameters of New Medicare Part A and B Benefit | ||||

| 100-150% of FPL | 150-250% of FPL | 250-500% of FPL | 500%+ of FPL | |

| Deductible | $150 | $300 | $600 | $700 |

| Coinsurance | 20% | 20% | 20% | 20% |

| OOP Limit | $1,500 | $3,000 | $6,000 | $7,000/$9,000* |

*After $7,000 of OOP costs, beneficiaries only pay 5% catastrophic coinsurance until reaching $9,000 of costs

Additionally, by providing Medicare beneficiaries with a limit on their out-of-pocket costs and more predictable cost-sharing it would also reduce the need for supplemental insurance, allowing many beneficiaries to save significant money by foregoing the purchase of a Medigap plan.

Therefore, in part because of the high cost of Medigap premiums, restricting Medigap supplemental insurance plans from covering first-dollar beneficiary cost sharing, in conjunction with a benefit redesign proposal, would reduce costs for the average Medicare beneficiary by $280 per year, according to an analysis performed by the Actuarial Research Corporation, all while also reducing deficits by $70 billion over ten years.

Specifically, the plan would restrict Medigap plans from covering any cost sharing within the new combined deductible and half of the enrollee's remaining cost sharing up to the new out-of-pocket maximum.

In addition to these changes, the plan would also change incentives for those with supplemental coverage through their employer by adding a 15 percent premium surcharge to those plans (the effects of this policy are not included in the distributional analysis). This policy would save an additional $30 billion over ten years, bringing the total ten-year savings to $100 billion, before allowing for any phase-ins of the various policies.

Importantly, this plan also provides significant new assistance for lower-income beneficiaries, making the reform highly progressive in its impact.

Little would change for seniors and people with disabilities earning less than 100 percent of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL) because almost all already have access to Medicaid wraparound coverage or the Qualified Medicare Beneficiary (QMB) program that covers all premiums and cost-sharing in Parts A and B.

Those with incomes just above 100 percent of FPL (up to 150 percent of FPL) would receive significant federal assistance with their cost-sharing burden, and would be subject only to a $150 deductible for Parts A & B (which is approximately the deductible for Part B alone today) and have their annual out-of-pocket costs capped at a maximum of $1,500. Beneficiaries with incomes between 150-250 percent of FPL would also benefit from reduced cost-sharing liability (a combined deductible of $300 and an out-of-pocket spending limit of $3,000).

Actuarial Analysis

A study from the Actuarial Research Corporation details exactly how this reform could work and how it would make both beneficiaries and the federal government better off.

Overall, the reform would save beneficiaries with incomes between 100-150 percent of FPL an average of $510 annually and those with incomes between 150-250 percent of FPL an average of $385 annually. Beneficiaries with higher incomes would still see their costs reduced, on average, but by a lesser amount (e.g., reduced by $130 for those with incomes above 500 percent of FPL).

Overall, roughly half of beneficiaries each would see their out-of-pocket costs increase or decline by more than $25 in a year, although a much greater percentage of lower-income beneficiaries would see their costs decline. Moreover, these policies will help an even higher percentage of Medicare beneficiaries if analyzed over a multi-year period. Looking at the impacts in one year obscures how many people would benefit from the new out-of-pocket limit over their full time in Medicare. While only 6 percent of beneficiaries face cost-sharing above $5,000 in a given year, over the course of 4 years, 13 percent face such high cost-sharing in a single year, and that number rises to 30 percent over 10 years.7,8

Largely due to introduction of out-of-pocket limits on annual cost-sharing, these proposals would also provide larger benefits and improve access to care for those in worse health.

Further Opportunities for Reform

Policymakers could also achieve further savings by applying the Medigap restrictions to other sources of supplemental coverage beyond those targeted in this plan. For example, CBO estimates that applying the first-dollar coverage restrictions to TRICARE-for-Life, the Medigap plan for non-disabled military retirees, could save an additional $30 billion over ten years. Mandating supplemental coverage from the Federal Employee Health Benefits' Program (FEHBP) being used to reduce premiums rather than cost-sharing could also save in the neighborhood of $10 billion. In addition, any of the parameters are dialable to achieve whatever fiscal or beneficiary savings targets there are.

Conclusion

The study shows that a Medicare benefit redesign would be positive for both beneficiaries and taxpayers. Not only would it result in lower out-of-pocket costs, it would also provide significant savings to help pay for a permanent SGR replacement and/or reduce health care spending.

1 Christopher Hogan. "Exploring the Effects of Secondary Insurance on Medicare Spending for the Elderly." Direct Research, LLC, for MedPAC, June 2009. https://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/contractor-reports/august2014_...

2 Ezra Golberstein, Kayo Walsh, Yulei He, and Michael Chernew. "Supplemental Coverage Associated With More Rapid Spending Growth For Medicare Beneficiaries," Health Affairs, May 2013. https://content.healthaffairs.org/content/32/5/873.full.pdf+html

3 Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. "Chapter 1: Reforming Medicare’s Benefit Design," June 2012. https://67.59.137.244/chapters/Jun12_Ch01.pdf

4 Gretchen Jacobson, Jennifer Huang, and Tricia Neuman. "Medigap Reform: Setting the Context for Understanding Recent Proposals," Kaiser Family Foundation, January 2014. https://kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medigap-reform-setting-the-context

5 Gretchen Jacobson, Jennifer Huang, Tricia Neuman, Katherine Desmond, and Thomas Rice. "Medigap: Spotlight on Enrollment, Premiums, and Recent Trends," Kaiser Family Foundation, April 2013. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/8412-2.pdf

6 Amanda Starc. "Insurer Pricing and Consumer Welfare: Evidence from Medigap," The RAND Journal of Economics, March 2014. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1756-2171.12048/abstract

7 See footnote 3.

8 House Energy and Commerce Committee. "Setting Fiscal Priorities," December 2014. https://energycommerce.house.gov/hearing/setting-fiscal-priorities