Temporary Expensing is a Budget Gimmick and a Bad Idea

One provision included in the $2.2 trillion "Unified Tax Framework" would allow companies to fully deduct or "expense" capital purchases other than structures, but only a temporary basis. Specifically, the framework calls for expensing to be in effect for "at least five years," implying the provision would expire thereafter. While expensing can be pro-growth, temporary expensing (outside of a recession) is poor tax policy that would do little to increase the size of the economy. From a budgetary perspective, temporary expensing masks the true cost of the provision and sets the stage for up to $600 billion of additional debt.

Temporary Expensing Masks Significant Costs and Sets the Stage for $600 billion of New Debt

Generally, tax and spending provisions are scored on a ten-year basis in order to give a sense of their structural impact on the medium-term budget deficit. Because of this ten-year scoring window, any temporary tax cut gives a somewhat misleading picture of its structural cost. This is particularly true of temporary expensing because it replaces the gradual deductibility of equipment (depreciation) and thus leads to higher tax collection after it expires because businesses would not take depreciation deductions on the equipment they expensed.

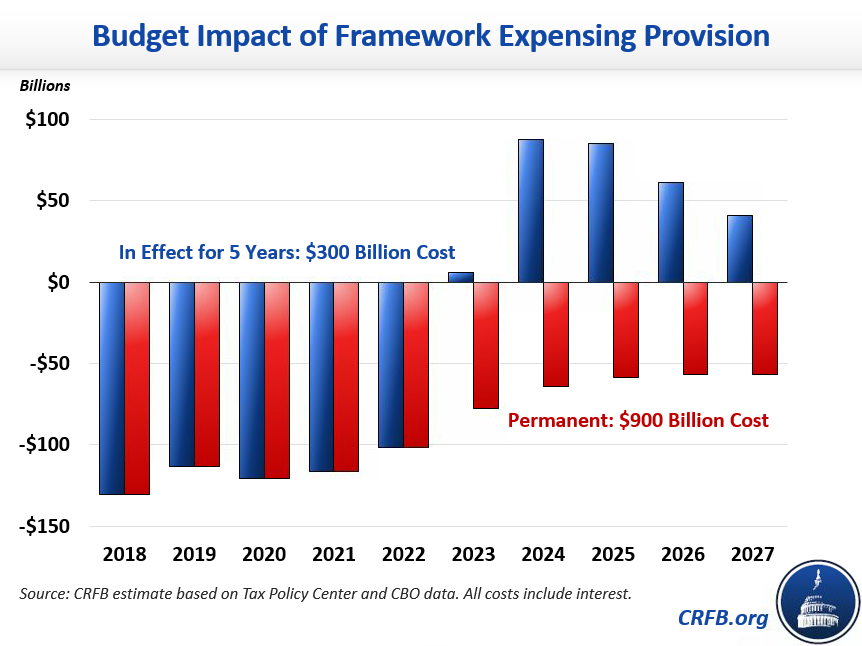

According to the Tax Policy Center, temporary expensing for machinery and equipment would cost about $540 billion (not including added interest costs) in the five years the provision was in effect but less than $200 billion over the ten-year budget window because revenues would increase after expensing expired.

In reality, such a proposal would set up a huge cliff designed to pressure policymakers into ultimately making expensing permanent. Including debt service, doing so would triple the cost of the provision.

Based on estimates from the Tax Policy Center, five-year expensing would add about $300 billion to the debt after a decade when interest is included. We estimate that continuing expensing for another five years would cost an additional $600 billion including interest, bringing the total increase in the debt to $900 billion. The Tax Foundation reached similar conclusions. Adding debt service costs to their estimates, temporary and permanent expensing for assets other than structures (inclusive of the framework's rate reductions) would cost roughly $410 billion and $920 billion, respectively.

Claiming a policy will expire halfway through the budget window in order to hide $600 billion in additional costs is a huge budget gimmick. And it is particularly dishonest to do so while also arguing that tax reform should be scored against a “current policy baseline” that assumes previous temporary tax cuts are permanent. Indeed, what would stop lawmakers five years from now from using the same "current policy baseline" gimmick to argue making temporary expensing permanent should be scored as having no cost?

Temporary Expensing is Bad Economic Policy

Not only is temporary expensing a budget gimmick, it is also poor tax and economic policy.

Permanent full expensing can increase long-run output by reducing the cost of capital and encouraging businesses to permanently increase investment. Temporary expensing, on the other hand, is more likely to encourage businesses to simply shift investments that would have otherwise been made in the future to the present, with no long-run increase in investment overall. That is precisely why the Framework's authors had previously stressed the importance of permanence.

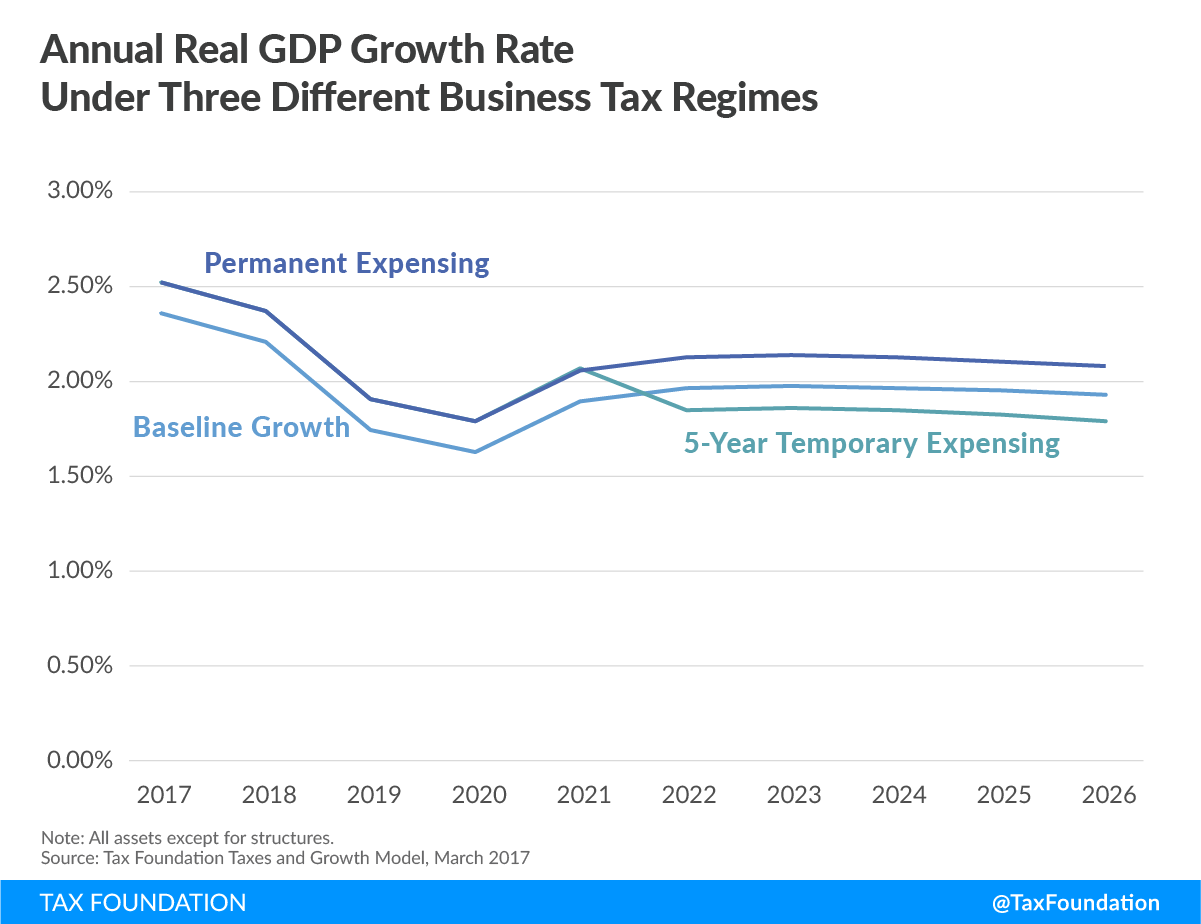

As a result, temporary expensing would likely accelerate economic growth in the first five years but slow growth in subsequent years. An estimate from the Tax Foundation – which tends to be a big fan of expensing – found that while permanent expensing of assets other than structures would increase the size of the economy by 1.6 percent after a decade, the boost from temporary expensing would be only 0.18 percent, and even that small increase would eventually disappear. They estimate permanent expensing would increase the annual growth rate in the last year of the budget window by about 0.16 percentage points, while temporary expensing would reduce it by around 0.12 points.

Source: Tax Foundation

While the economic effects of temporary expensing might be modestly better if companies believed the policy would eventually be made permanent, the surrounding uncertainty would still make it far less effective than if it were honestly made permanent in the first place. Indeed, the only possible argument in favor of temporary expensing is as economic stimulus to help the economy out of a recession (though there is disagreement over whether or not more generous write offs make for effective stimulus); it makes no sense at a time when the economy is essentially at full employment.

Any Expensing Policy Should be Permanent and Coupled with Limits on Interest Deductibility

Rather than allowing temporary full expensing, tax reformers should pursue a permanent policy, even if it does not go as far as full expensing. For example, permanent bonus depreciation would essentially allow for 50 percent expensing of equipment at a similar ten-year cost to five years of full expensing, but it would not set up a massive budget gimmick and would be far more pro-growth than temporary 100 percent expensing.

Policymakers could also adopt permanent full expensing of equipment and even accelerate cost recovery for structures, so long as they offset the cost of doing so. The most logical offset, of course, would be to limit or eliminate the deductibility of interest expenses. The combination of expensing and interest deductibility would lead to a massive negative tax rate on debt-financed investment, encouraging overleveraging and effectively subsidizing investments that might otherwise be uneconomical. A 2014 Congressional Budget Office report estimated that adopting full expensing for all capital investments (including structures) without limiting interest deductibility would lower the effective marginal tax rate on debt-financed investments from -6 percent to -61 percent for corporations, and from 8 percent to -34 percent for pass-through entities; that is, more than one-third of the investment return would come in the form of a tax subsidy.

Limiting interest deductibility could correct this problem and help equalize the tax treatment of debt and equity while also ensuring expensing doesn't add massively to the debt now or in the future. The Framework does call for some limitation of interest deductibility, but it does not specify how much or what it would look like.

***

The Framework’s proposal for temporary expensing makes no sense on policy grounds. It is simply being used as a budget gimmick to hide hundreds of billions of dollars in future tax cuts. If policymakers think adopting permanent expensing is a worthwhile policy, they should openly propose doing so and come up with legitimate pay-fors to offset its costs. They shouldn’t resort to budgetary smoke and mirrors to make their proposal seem slightly less fiscally irresponsible than it already is.