Senate Finance Prescription Drug Bill Would Reduce Deficits by $100 Billion

The Senate Finance Committee recently approved by a 19-9 vote a prescription drug bill, the Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act, that the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) preliminarily estimates will save at least $100 billion over ten years. The bill would make several changes to Medicare and Medicaid drug policies with the intent of lowering prices for those programs and across the health care system. This bill adds to several recent bills that have been moving through Congress, including the Senate Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions (HELP) Committee health care bill, a House prescription drug and insurance exchange bill, and multiple Senate Judiciary Committee prescription drug bills. At a time when lawmakers are adding substantially to the debt, the bill represents a positive step on reducing health care spending and the deficit.

While the legislation includes a number of policies to reduce drug costs, the two most significant proposals include a reform to Medicare Part D’s benefit design and a limit on Part D spending for drug prices that grow faster than inflation.

Currently, Medicare Part D insurers must offer a basic plan where seniors pay a $415 deductible, 25 percent of costs up to a "donut hole," 25 to 37 percent of costs up to a "catastrophic cap," and 5 percent of all catastrophic costs. The insurance plan covers all the remaining costs up to the donut hole but only covers a small fraction of costs after that. The remainder is covered with rebates from drug manufactures up to the catastrophic cap and government re-insurance above that cap. This generous reinsurance has been criticized for driving up drug prices and costs.

The bill would re-arrange this design to provide a uniform 25 percent/75 percent split in cost responsibility between enrollees and insurers up through the catastrophic phase, at which point beneficiaries would no longer face any out-of-pocket costs. Instead of catastrophic costs being split between beneficiaries paying 5 percent, reinsurance covering 80 percent, and plans covering 15 percent, a much larger share would be shifted to the plans. The proposal would phase down reinsurance to cover only 20 percent of costs for name brand drugs, while insurers would cover 60 percent and drug manufacturers cover the remaining 20 percent. Generic drugs would ultimately be split 60 percent/40 percent between the insurer and reinsurance. These changes, which are similar to ones the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) has recommended, are intended to give insurers and manufacturers more incentive to keep costs down and to reduce out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries. CBO estimates that the new benefit structure would save $35 billion over ten years while reducing enrollee cost sharing by $21 billion and premiums by $1 billion.

Proposed Changes to Part D Benefit

| Payer | Deductible | Initial Coverage | Donut Hole | Catastrophic Phase | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current Law/Proposed | Current Law/Proposed | Current Law | Proposed | Current Law | Proposed | |

| Beneficiary | 100% | 25% | 25% (37%)* | 25% | 5% | 0% |

| Insurance Plan | 0% | 75% | 5% (63%)* | 75% | 15% | 60% |

| Manufacturer | 0% | 0% | 70% (0%)* | 0% | 0% | 20% (0%)* |

| Reinsurance | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 80% | 20% (40%)* |

Source: Senate Finance Committee.

*First number represents name brand drug cost responsibility while number in parentheses represents generic drug cost responsibility.

At the same time, the bill would require manufacturers to pay rebates in Medicare Parts B and D if their drug prices increase faster than inflation. This policy is intended to limit Medicare's fiscal exposure to large price increases. Importantly, Medicaid already includes inflation rebates; applying them to Part B drugs would save $11 billion over ten years, while applying them to Part D drugs would save Medicare $58 billion and would have indirect effects on private and Medicaid spending that CBO hasn't estimated yet. However, CBO has indicated that the Part D rebates would produce additional savings in private insurance and additional costs in Medicaid.

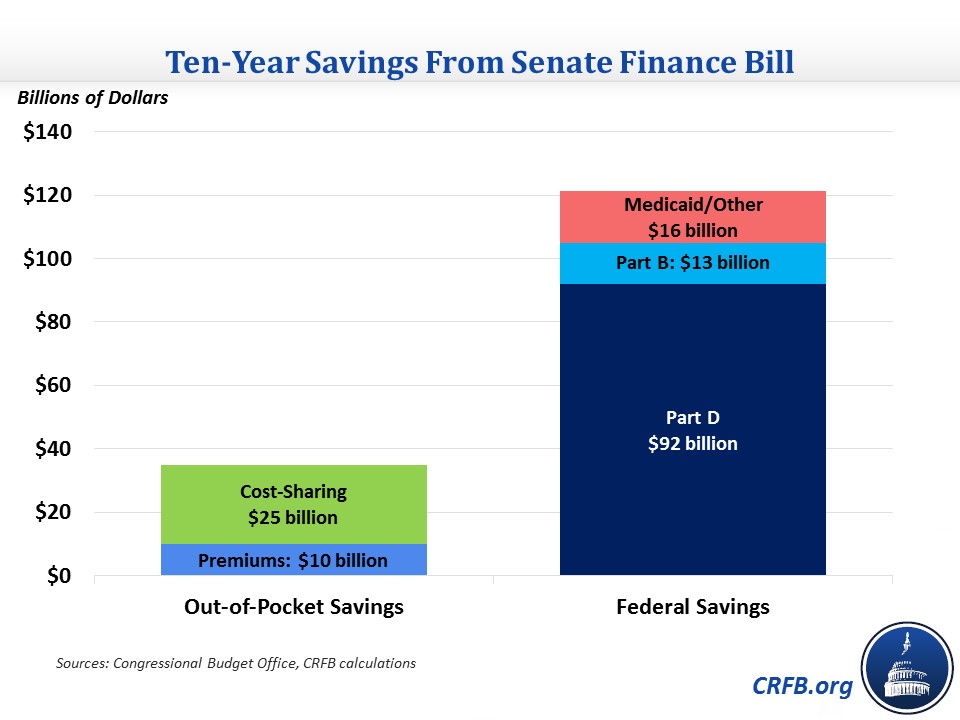

According to CBO, these two policies alone would reduce drug costs of the federal government and for beneficiaries. It estimates $92 billion of Part D savings from these two policies and over $30 billion of savings to enrollees from lower premiums and cost sharing. Based on some rough assumptions, we estimate total beneficiary savings from the bill would exceed $35 billion. Total federal savings would exceed $100 billion.

In addition to the policies above, the bill includes several smaller changes to Medicare drug payment policy. For example, it would include the value of coupons provided to patients in the Average Sales Price (ASP) that is the basis for Part B payments ($1.5 billion savings), limit add-on Part B payments (usually 6 percent of ASP) to $1,000, pay existing hospital outpatient departments at the rate of physician offices for Part B drugs ($505 million savings), require manufacturers to refund discarded single-vial drugs, and codify the reduction in payment rates for new drugs that use the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) ($230 million savings). These changes would generally encourage more efficient use of drugs in outpatient settings.

Budgetary Effect of Prescription Drug Pricing Reduction Act

| Policy | Ten-Year Savings/Cost (-) |

|---|---|

| Redesign Part D benefit structure | $34.6 billion |

| Require manufacturers to pay inflation rebates in Part D | $57.5 billion* |

| Require manufacturers to pay inflation rebates in Part B | $10.7 billion |

| Increase maximum rebate from 100% to 125% of drug price | $12.5 billion |

| Exclude authorized generics from Medicaid rebate calculation | $3.2 billion |

| Include patient coupons in ASP calculation | $1.5 billion |

| Prohibit PBM spread pricing in Medicaid | $1 billion |

| Equalize Part B drug payments for existing hospital outpatient departments and physicians | $0.5 billion |

| Reduce WAC-based Part B drug payments from 106% to 103% of WAC | $0.2 billion |

| Other policies | -$0.1 billion^ |

| Sum of Policies as Currently Estimated | $121 billion |

| Total as Articulated by CBO | >$100 billion** |

Source: Congressional Budget Office.

*Savings estimate is incomplete because it does not include the indirect effects of the policy on private insurance and Medicaid spending.

^Excludes five policies that CBO has not estimated, four of which it expects would reduce spending and one whose effect direction is unclear.

**Total savings as currently estimated is $121 billion, but the estimate is incomplete. CBO expects its full estimate would show savings of at least $100 billion.

The bill also includes changes to how Medicaid rebates are calculated. Current Medicaid policy includes both the inflation rebates mentioned above and rebates calculated based on a percentage of the drug's price. The bill would increase the maximum rebate a manufacturer could provide from 100 percent of the drug's price to 125 percent, saving $12 billion over ten years. This change would raise the point where manufacturers would avoid paying additional inflation rebates because the price has increased enough to reach the limit. It would also exclude authorized generic drugs from rebate calculations, which would increase the prices on which rebates are based and save $3 billion, and prohibit spread pricing for pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) participating in Medicaid, saving nearly $1 billion.

In addition to these policies, the bill includes several transparency and disclosure requirements for drug prices, rebates, and other aspects of the pharmaceutical supply chain that CBO expects would have little or no effect on the federal budget.

Overall, CBO's preliminary estimate of the bill comes to $121 billion of savings over ten years, but CBO doesn't estimate savings from four policies it expects would reduce spending (and one whose effect is unclear). Additionally, as mentioned above, it doesn't include indirect effects from the Part D inflation rebates, so the score is not complete. CBO says that it expects the complete score would show savings of at least $100 billion.

The Senate Finance bill is one of the most significant health savings efforts this decade, especially for one that is being done on a bipartisan basis. Along with bipartisan proposals to reduce surprise billing and reform provider payments, this bill offers a path forward to putting public and private health care spending on a more sustainable track.