Senate Budget Committee Holds Hearing on Raising Revenue to Save Social Security

On July 12, the Senate Budget Committee held a hearing titled "Protecting Social Security for All: Making the Wealthy Pay Their Fair Share" to discuss the looming impending insolvency of the Social Security trust funds and revenue options to secure solvency. The hearing included testimony from Social Security Administration Chief Actuary Stephen Goss, Director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) Phillip Swagel, Kathleen Romig of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Amy Hanauer of the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, and Andrew Biggs of the American Enterprise Institute. Committee Chairman Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and Ranking Member Chuck Grassley (R-IA) also provided statements.

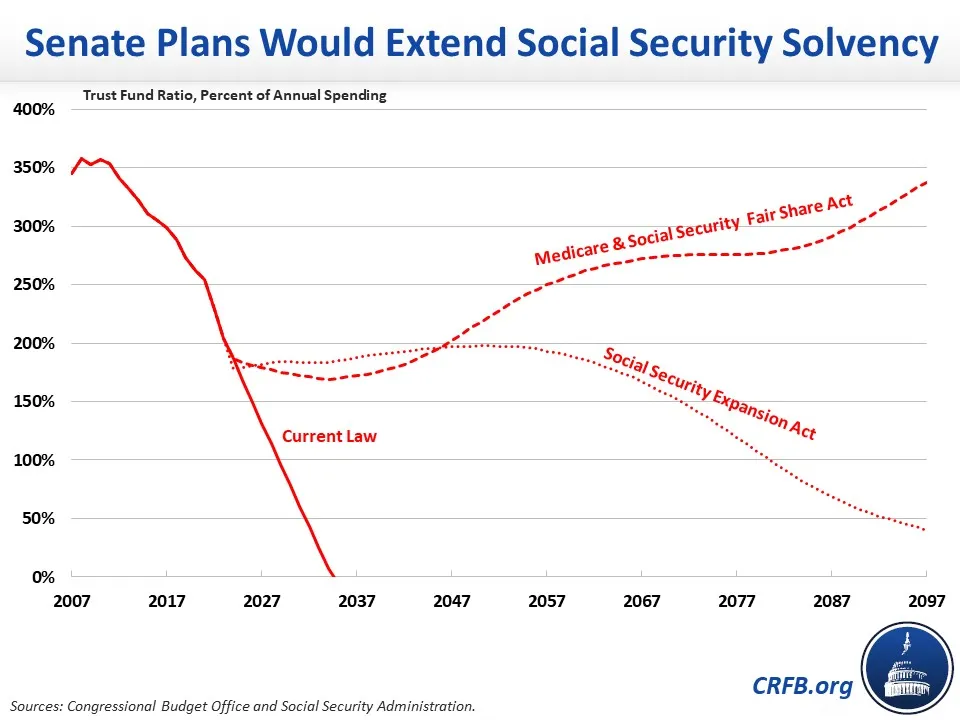

Much of the hearing focused on Chairman Whitehouse's (D-RI) Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act and Senator Bernie Sanders's (I-VT) Social Security Expansion Act. Currently, Social Security is funded primarily with a 12.4 percent payroll tax on wages up to about $160,000 (indexed to wage growth). The Whitehouse plan would apply the tax to all wages above $400,000 and also expand the tax to apply to most investment and business income for those higher earners. The Sanders bill would adopt a similar set of tax increases but apply them above $250,000 of income. Neither plan would count income subject to these new taxes toward the benefit calculation, and both would freeze the thresholds so that eventually all wage income (and most investment and business income) is subject to the payroll tax.

Although the Social Security Expansion Act would raise significantly more revenue than the Social Security Fair Share Act, it would do less to achieve solvency since it would repurpose nearly two-fifths of that revenue toward benefit expansions. In particular, the Social Security Expansion Act would modify the Social Security benefit formula to increase benefits for most beneficiaries by about $2,400 per year. It would also index current benefits to a faster-growing (and less accurate) measure of inflation known as the Experimental Consumer Price Index for Americans 62 Years of Age and Older (CPI-E).

Summary of the Medicare and Social Security Fair Share Act and Social Security Expansion Act

| Policy | Medicare & Social Security Fair Share Act | Social Security Expansion Act |

|---|---|---|

| Apply 12.4 percent payroll tax to wages above $250,000/$400,000 | 63% | 68% |

| Apply 12.4 percent payroll tax to some investment and business income | 50% | 79% |

| Increase benefits by $2,400 per year for most retirees | n/a | -40% |

| Use faster CPI-E to calculate annual cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) | n/a | -11% |

| Other Benefit Expansions | n/a | -4% |

| Reduction in 75-Year Solvency Shortfall | 112% | 91% |

| Memo: Reduction in 75th Year Shortfall | 111% | 84% |

Sources: Social Security Administration and Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Numbers may not sum due to rounding.

As a result of these policies, the Social Security Administration estimates both plans would extend the life of the theoretically combined trust funds – scheduled to be insolvent in just 11 years – beyond the 75-year projection window. However, the Social Security Expansion Act would not meet the Trustees' definition for long-term solvency, as the fund would run out of reserves shortly after the end of the projection window.

Importantly, the estimated effect of these plans on Social Security solvency significantly overstates their net fiscal impact. The increase in taxes on employer payrolls and capital gains income in particular will significantly reduce taxable income to the rest of government (including by raising the capital gains rate above its revenue- maximizing level) and thus increase budget deficits outside of Social Security. Although we have not estimated the general revenue loss associated with these proposals, a prior (and somewhat different) version of the Social Security Expansion Act would lose one-third of its new revenue to lower income taxes. If this same proportion applied to the new bill, roughly half of the net solvency gains would be the result of an indirect general revenue transfer.

Even still, Senators Whitehouse and Sanders both deserve praise for introducing bills that would avoid insolvency over the next 75 years. Although there may be better approaches that don't result in significant general fund losses, these bills represent significant improvements over the alternatives of more borrowing or deep across-the-board benefit cuts in just a decade.

As we recently showed, failing to restore Social Security solvency would mean a $17,400 benefit cut for a typical couple retiring in 2033. The witnesses and committee members agreed that time is running out to save Social Security and action must be taken soon to prevent across-the-board benefit cuts and give workers and retirees time to plan and adjust.