Can Post-Acute Care Reforms Save the Medicare Trust Fund?

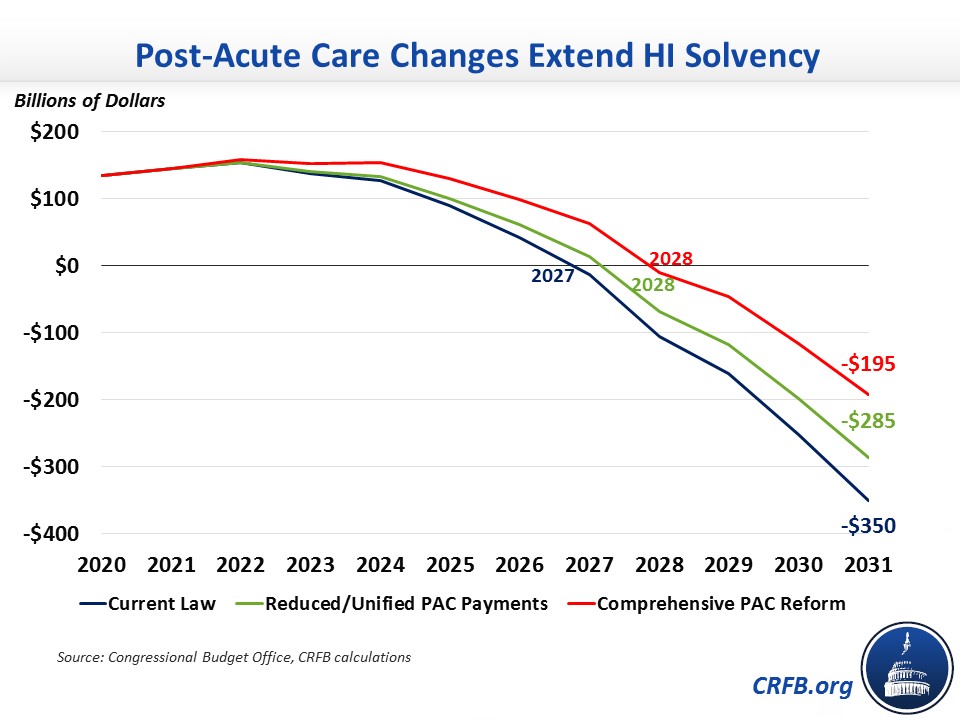

The Medicare Part A Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund will be insolvent within five years according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Medicare Trustees. CBO estimates the trust fund will run cumulative deficits of about $510 billion over the next decade, leading to a $350 billion solvency gap through 2031, after accounting for current trust fund holdings. Reducing post-acute care costs – which has been proposed by Presidents of both parties and experts like the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) – would help improve HI's financial state.

Post-acute care (PAC) refers to care that aids in the recovery from an injury or illness following a hospitalization. There are four basic types of PAC settings: skilled nursing facilities (SNFs, or nursing homes), inpatient rehabilitation facilities (IRFs), long-term care hospitals (LTCHs), and home health agencies (HHAs). All four settings are covered under Medicare Part A except for home health care, which is covered under Part A for the first 100 days after a hospitalization or SNF stay and under Part B in other circumstances or beyond 100 days. Each setting has its own prospective payment system (PPS) that compensates providers based on the type and severity of care needed for its patients.

PAC spending in traditional fee-for-service Medicare totaled $57 billion in 2020, with $46 billion of that in Part A. A majority of that spending occurred in SNFs ($28 billion), followed by smaller amounts in IRFs ($8 billion), HHAs ($6 billion), and LTCHs ($3 billion). PAC spending was about one-quarter of total Part A spending in 2020.

Post-acute care is a target for potential savings because there is evidence of excessive profits for PAC providers. MedPAC estimated that Medicare payments over the 2008-2018 period exceeded costs by 10-15 percent for PAC providers other than LTCHs, and those margins have only increased to 15-20 percent in 2020.

Furthermore, there is evidence of a wide variation in PAC spending across the country not tied to differences on health outcomes. Research suggests that much of the geographic variation in overall Medicare spending can be attributed to variation in PAC spending. Even relative to the commercial market, there is higher PAC spending per beneficiary in Medicare, with no difference in hospital readmission rates.

There are many options for reforms. Presidents Obama and Trump, as well as MedPAC, have consistently proposed reductions in payment rates or payment growth for PAC providers, as well as other changes to promote care coordination and more uniform payments across settings.

| Policy | Total Savings | Part A Savings | % of Solvency Gap | % of Deficit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduce Post-Acute Care Provider Payments | ||||

| Reduce payment updates and move to unified PAC payments (Trump) | $80B | $65B* | 18% | 13% |

| Reduce payment updates by 1.1% per year (Obama) | $70B | $60B* | 17% | 12% |

| Reduce SNF, HHA, and IRF payments by 5% (MedPAC) | ~$60B^ | ~$50B | 14% | 10% |

| Bundle Payments for Post-Acute Care | ||||

| Bundle inpatient and PAC payments (5% savings target) (CBO) | $45B | $40B* | 11% | 7% |

| Bundle PAC payments (2.85% savings target) (Obama) | $10B | $7B* | 2% | 1% |

| Home Health Changes | ||||

| Require enrollees to pay 10% of home health costs (CBO) | ~$35B | ~$10B | 3% | 2% |

| Require a $150 home health copay per episode (Modified MedPAC) | ~$10B | ~$5B | <1% | <1% |

| Shift Part A home health spending to Part B | ~$20B | ~$80B | 23% | 16% |

| Apply cost-sharing for other PAC/Part B services to home health | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Other Changes | ||||

| Enact value-based purchasing for all PAC settings (House) | ~$15B | ~$10B | 4% | 2% |

| Narrow the exception for site-neutral LTCH payments (Trump) | $5B | $5B | 1% | 1% |

| Increase IRF condition rule from 60% to 75% (Obama) | $2B | $2B | 1% | <1% |

| Equalize IRF and SNF payments for certain conditions (Obama) | $1B | $1B | <1% | <1% |

| Adopt unified PAC payments, home health co-pay, smaller site-neutral/IRF changes, and shift home health to Part B | $115B | $155B | 44% | 30% |

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, CRFB calculations

*Absent further information, this estimate assumes savings are proportional across post-acute care settings.

^Rough estimate based on five-year savings ranges MedPAC provides for each policy

The most fundamental reforms would address the misaligned incentives that arise from having payment differences based on the location of treatment instead of the actual care a patient receives, and from splitting acute care payment from the related post-acute care.

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is currently required by law to propose a plan, by the end of 2022, for transitioning to a unified payment system for all four PAC settings. The end goal would be site-neutral payments that vary only by patient characteristics. In a recent report, MedPAC offered suggestions to CMS about how that might be done in a way that incorporates a value incentive program, in order to reward outcomes and performance while transitioning away from fee-for-service incentives.

President Trump's final budget for fiscal year (FY) 2020 contained a proposal to enact a unified payment system, along with a reduction in payment updates during the transition, which was estimated to save nearly $80 billion overall and likely around $65 billion for Part A specifically.

Another option would be to bundle payments for inpatient care and PAC together, making a single payment for an entire episode of care rather than separate payments to different facilities and doctors involved. The intent of bundled payments is to improve care coordination and efficiency. In 2013, CBO estimated that bundling payments for inpatient care and 90 days of PAC with a savings target of 5 percent would save $45 billion over ten years (likely $40 billion in HI), with about two-thirds of the savings coming from PAC. President Obama also proposed bundling payments for PAC with a phased-in 2.85 percent savings target, which CBO estimated would save nearly $10 billion. Both estimates were published several years ago, so it is unclear what a similar proposal would currently be estimated to save.

Other proposals would simply reduce PAC payments without changing the underlying payment systems. President Obama's final budget for FY 2016 proposed reducing payment rate increases by 1.1 percent per year for ten years for IRFs, LTCHs, and HHAs, while reducing increases for SNFs by 1-2.5 percent per year for eight years. CBO estimated this policy would save $70 billion over ten years and roughly $60 billion for the HI trust fund. This year, MedPAC recommended reducing payment levels by 5 percent for SNFs, IRFs, and HHAs while leaving LTCH payments unchanged from current law. These recommendations would likely save similar amounts as the Obama budget proposal.

Lawmakers could also add cost-sharing to home health care to bring it in line with other services. Spending on home health care isn't subject to cost-sharing beyond the Part A and B deductibles, unlike other Part A PAC services that have daily copayments and other Part B services that usually have 20 percent coinsurance. A 2008 CBO option would have made enrollees responsible for 10 percent of the total cost of a home health care episode, saving about 15 percent of projected home health spending over ten years, or roughly $35 billion based on current projections (a bit over $10 billion for HI specifically). MedPAC and President Obama both proposed requiring a copay per home health care episode that excluded PAC use and, in the Obama proposal, exempted existing enrollees, with savings below $5 billion over ten years. Based on these estimates, a copay with no exemptions would save roughly $10 billion overall and less than $5 billion for HI specifically. Lawmakers could also make cost-sharing more uniform by applying the other PAC services' copay amounts to Part A home health and applying the 20 percent coinsurance to Part B home health.

Moving the Part A portion of home health to Part B would be another way to improve HI's finances. While this would largely represent a shift in spending of $85 billion over ten years out of Part A, it would also produce net deficit reduction overall because Part B premiums are set at one-quarter of program costs. Therefore, shifting home health spending to Part B would save roughly $20 billion due to higher Part B premiums. Lawmakers could ultimately erase any net savings by exempting the shifted spending from premium calculations, or they could further increase savings by combining the shift with any of the above payment or cost-sharing policies.

There are several other options lawmakers have at their disposal to reduce PAC costs. One option from 2015 House legislation would establish value-based purchasing programs for each PAC provider, building on the SNF value-based purchasing (VBP) program enacted in 2014. The programs would have withheld a certain amount of payments each year (3 percent initially, increasing to 8 percent) and given a portion back in bonuses to providers performing highly on cost-per-capita measures. Based on the original score of the SNF VBP program, we estimate this legislation would save $15 billion over ten years and $10 billion for HI, assuming the same five-year delay in implementation as the original legislation (if implemented next year, savings would be $30 and $20 billion, respectively).

Another option from President Trump's budgets would increase the amount of time a patient must spend in an ICU prior to a LTCH stay from three to eight days in order to qualify for an exception to site-neutral payments, which would save $5 billion. A proposal from President Obama's budgets would increase IRF designation requirements by increasing the share of patients IRFs must admit that have certain conditions from 60 to 75 percent, saving $2 billion. Finally, an older Obama budget proposal would equalize payments between SNFs and IRFs for pulmonary, hip, and knee conditions, saving $1 billion.

Overall, post-acute care reforms could substantially improve the HI trust fund's financial state. For example, adopting the PAC payment reductions and unified payment system proposed by the Trump White House would extend the insolvency date by one year to 2028, close one-fifth of the ten-year solvency gap, and erase nearly 15 percent of ten-year deficits. A more comprehensive reform including that payment range, a home health co-pay and shift into Part A, and the smaller Obama and Trump proposals mentioned in the previous paragraph would also push the insolvency date to 2028, close 45 percent of the solvency gap, and erase 30 percent of ten-year deficits.

Reforms to Medicare PAC spending won't be large enough to prevent HI trust fund insolvency alone, but along with other options like reducing Medicare Advantage payments, they can be a significant part of the solution. With insolvency only five years away, lawmakers must get to work on HI trust fund solutions.