Donald Trump's Treasury Buyback Plan

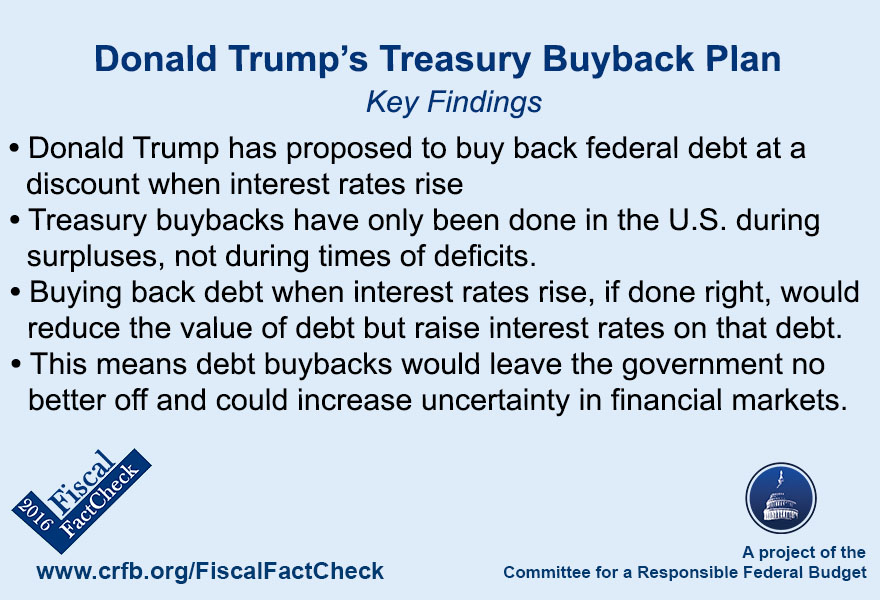

Last week, Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump made waves in a CNBC interview when he seemed to indicate that he would seek to renegotiate the terms of Treasury securities if interest rates rose significantly, saying “I would borrow, knowing that if the economy crashed, you could make a deal.” He later clarified that he did not mean that he would default on the debt and added that “This is the United States government….you never have to default because you print the money.” Instead, he said he meant that, “if we can buy back government debt at a discount, in other words, if interest rates go up and we can buy bonds back at a discount — if we are liquid enough as a country, we should do that.” This action, known as a Treasury buyback, would have the government purchase older-issued bonds at a discount and allow investors whose bonds are purchased to get newly-issued securities with higher interest rates (buybacks can be used for other purposes as well). Ultimately, as we explain below, this move would reduce the size of federal debt only on paper and would not change the federal government’s fiscal situation much. This post will explain Treasury buybacks and discuss Trump’s other comments about debt and default.

Background

Since the 2008 financial crisis and the Federal Reserve’s decision to cut the federal funds rate to near-zero, interest rates on Treasury securities have been very low by historical standards. For example, the ten-year Treasury rate is currently below 2 percent, a level not achieved prior to the Great Recession since at least 1953. Rates have remained low for several years due to continued economic weakness and the Federal Reserve’s decisions to hold the federal funds rate below 0.5 percent and hold longer-term Treasury securities on its balance sheet. These conditions are not expected to continue, as the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the ten-year Treasury rate will rise gradually to 4.1 percent by 2019.

The Treasury Department has been attempting to take advantage of the low rates by issuing a greater share of longer-term securities, thus locking in more federal debt at lower rates. After dipping to a low of 4 years during the worst of the Great Recession, the average maturity of federal debt has steadily increased to 5.75 years (69 months) as of the end of March. Still, even with the increase in average maturity, about two-thirds of Treasury securities will mature within 5 years, so interest rate increases would clearly raise the government’s interest burden in the short term and beyond.

Treasury buybacks have been done a few times historically but not for the reason Trump suggests. Rather they have been done during periods of large surpluses most recently being undertaken from 2000 to 2002. The purpose of these buybacks has been to bring the amount of Treasury securities in line with borrowing needs and ensure that new more highly-traded Treasury securities continue to be issued. Coincidentally, the Financial Times reported last week that the Treasury Department was looking into doing buybacks for the latter purpose: to replace older securities that are traded less frequently with new securities that are bought and sold more readily, making the Treasury market more fluid. A 2007 paper from the New York Federal Reserve’s Kenneth D. Garbade and Matthew Rutherford identified two other reasons to undertake buybacks: smoothing out cash balances, which can fluctuate in high surplus or deficit months, and smoothing out Treasury auctions.

How Trump’s Buyback Could Work

Unless the fiscal situation changed dramatically, Donald Trump’s proposed buybacks would be occurring in the context of deficits rather than surpluses. These buybacks could happen if interest rates increase as expected, providing an opportunity to buy back old debt at a discount. When interest rates rise, it allows for the federal government to buy back previously-issued Treasuries at below their original value so that investors could buy new bonds with higher interest rates. For example, the government could buy back $100 worth of old securities with an interest rate of 4% at, say, $80 and issue $80 of new debt at a 5% interest rate to finance the purchase. The result is that the total value of federal debt would fall, but the higher interest rates on the new bonds would cause the federal government’s interest payments on the debt to remain about the same as before. In short, the size of federal debt would fall, but the average interest rate on that debt would increase.

Ultimately, this would have little effect on the federal government’s fiscal situation. The Treasury Department is concerned with minimizing interest costs, not debt, and buybacks would only change the composition of how interest costs would be determined (lower debt, higher interest rates), not the resulting interest cost. If the federal government were running surpluses, it would make sense to use extra cash on hand to buy back debt and lower the federal government’s interest burden as its borrowing needs declined. But simply replacing old debt with new debt would have little effect. There could actually be a slight cost if the move stokes uncertainty in the Treasury market.

Printing Money and Default

In explaining his earlier comments, Donald Trump argued that the federal government would never have to default because it could always print money. In a mechanical sense, this is true: because the US has its own currency and monetary policy, it can print money to buy bonds if investors are unwilling to buy debt at all or only at very high interest rates (assuming that the Federal Reserve is willing to print the money to do so). Of course, there are clear limits to this policy, and running up large amounts of debt and financing it by printing money would cause a jump in inflation and interest rates. If this continues indefinitely, a default of some kind, with its disastrous implications for the economy, could actually look to be the more attractive option to end hyperinflation. In that sense, the federal government would have its hand forced to default because of the economic situation, but it would not strictly run out of money as some other countries that don’t have their own currency have faced.

*****

Donald Trump’s original comment indicating he would renegotiate Treasury bonds caused panic among economic and financial experts, but he ultimately meant a policy that would be much less consequential. Treasury buybacks can be useful in some circumstances for the reasons identified above, but buying old debt at a discount and financing it with new debt would not produce a meaningful change in the government’s fiscal situation. Only in the context of surpluses and declining debt would buybacks be able to actually reduce interest spending on the debt, and Trump’s proposals would move the government further away from that, not closer.