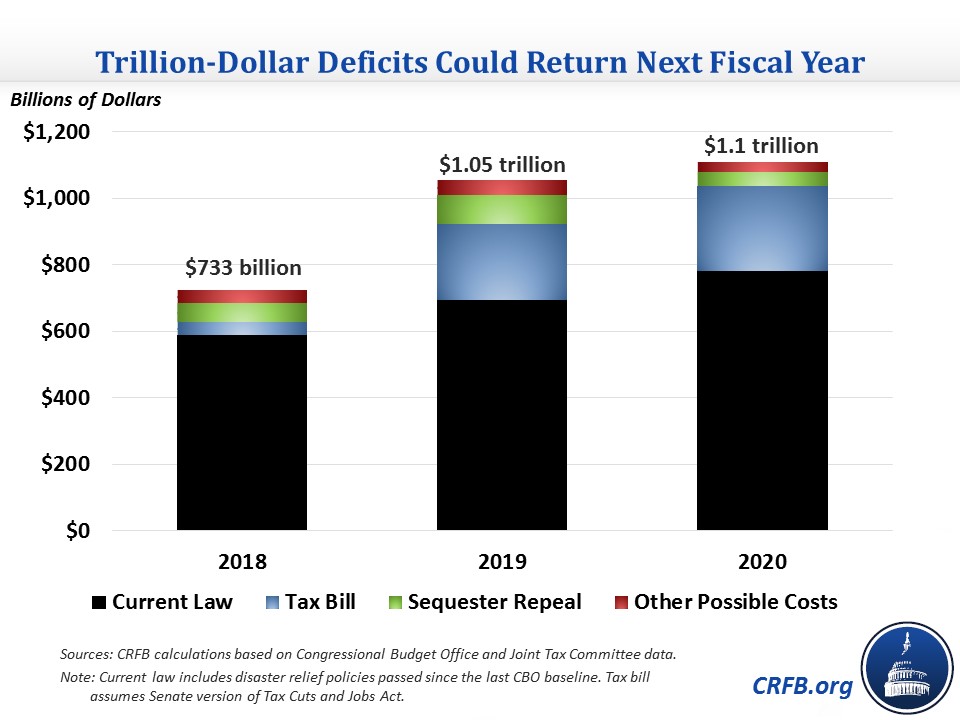

December Legislation Could Bring Back Trillion-Dollar Deficits

Congress has a lot on its plate this holiday season. Sadly, they seem far more focused on legislation to increase our post-war record-high national debt than reduce it. If they aren't careful, we estimate legislation under consideration could bring back trillion-dollar deficits by next year – Fiscal Year (FY) 2019 (FY 2018 began on October 1).

Even under current law, deficits are likely to reach almost $600 billion this year and $700 billion next year. By our estimate, a combination of tax cuts, sequester relief, and other changes would increase deficits to $1.05 trillion by 2019 and $1.1 trillion by 2020. Tax cuts and sequester relief alone would be enough to bring back trillion-dollar deficits by 2019, and tax cuts by themselves would bring them back by 2020. The total cost of all of these policies would be around $1.8 trillion over ten years.

Driving this deficit increase are several legislative proposals that could add to the debt. Our hope is that policymakers will fully offset all of these packages. A more likely scenario is that some pieces are offset over time but most are deficit-financed. There is also some risk that practically everything is deficit-financed. The legislation that may be enacted next month includes:

Tax Cuts and Reforms: The Senate tax bill currently under discussion would cost about $1.4 trillion over a decade, including over $500 billion in the first three years alone. That cost could increase by an additional $500 billion if various expiring provisions are continued. With interest, the result would be $2.2 trillion of debt over the next decade. Tax reform is needed to help grow the economy, but it should be at least deficit-neutral to maximize its growth effect and avoid worsening deficits. Yesterday, we suggested a number of possible improvements to make the bill responsible.

Sequester Relief: With sequester-level caps slated to return, reports indicate a potential $200 billion deal to fully repeal the sequester for two years and then further increase discretionary spending. Such a deal should be fully offset, and our Mini-Bargain To Improve the Budget proposes adopting a more accurate measure of inflation government-wide to offset the cost of permanent (rather than two-year) sequester relief; it also offers $400 billion of other potential offsets – everything from Medicare reforms to federal retirement changes to user fees.

Disaster Relief: The Trump Administration has requested $44 billion of additional disaster relief funding to deal with the impact of Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, and additional requests are likely. To its credit, the Administration has proposed offsetting this and other funding with $60 billion of spending cuts, including by extending the mandatory sequester for two years. Policymakers should embrace these or other offsets (though we fear they won't). In our Mini-Bargain, we propose $100 billion of potential offsets to finance disaster relief.

Obamacare Tax Delays: In 2015, lawmakers temporarily removed or delayed three taxes passed under the Affordable Care Act (ACA or "Obamacare") to help finance its spending increases. Two of these taxes – the medical device tax and health insurers tax – are scheduled to go into effect next year; at the same time, the ACA originally called for tightening limits on health cost deductibility next year. Policymakers may choose to further delay these taxes and perhaps the implementation of the "Cadillac" tax on high-cost plans, which is scheduled to take effect in 2020. If all four tax changes were delayed for two years, it would cost over $50 billion over ten years. However, Congress should end this process of continued delays and either allow these taxes to go into effect or permanently replace them with other savings. For example, they could replace the Cadillac tax with a modest limit on the employer health exclusion.

Tax Extenders: The 2015 PATH Act was designed to address all temporary tax extenders once and for all. Many were made permanent, while some were extended temporarily and put on track to expire (which they did at the end of 2016). However, rumors suggest that Congress may bring back some of these expired tax provisions. If all extenders not included in tax reform were continued through the end of 2018, it would cost roughly $20 billion. Rather than continuing to add to the debt, lawmakers should let most of these extenders remain expired – and any they want to continue should be addressed in tax reform or at least in a fully-offset tax package.

CHIP and Health Spending Extenders: The Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) authorization expired at the end of September, and both the House and Senate have proposed a five-year reauthorization, though only the House would offset the cost of the extension. In addition, several other temporary health extenders will expire at the end of the year. If a five-year CHIP reauthorization and two-year extenders deal were passed, the cost would be $20 billion. The House's proposed offsets are a promising start, and many other health options are available.

| Policy | Potential Ten-Year Deficit Effect |

|---|---|

| Tax Bill | $1.4 trillion |

| Sequester Relief | up to $200 billion |

| Disaster Relief | $45 billion or more |

| Obamacare Tax Delays | $55 billion for two years |

| Tax Extenders | $20 billion for two years |

| CHIP and Health Spending Extenders | Up to $20 billion |

| Potential Interest Costs | Up to $370 billion |

| Total | Up to $2.2 trillion |

| Memo: | |

| Additional cost from permanent extension of temporary provisions above (including interest) | +$1.8 trillion |

| Total, cost if temporary provisions above are permanently extended (including interest) | up to $4.0 trillion |

Sources: Congressional Budget Office, Joint Committee on Taxation.

Our Mini-Bargain to Improve the Budget offers a fiscally responsible path forward for most of these policies. Unfortunately, the current discussion seems more focused on increasing the debt than reducing it.

If policymakers adopt only the Senate tax bill without offsets, that alone would be enough to increase debt held by the public to 97 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by 2027 (debt would exceed the size of the economy two years later). Unpaid-for sequester relief and other policies above would be enough to increase that debt ratio to 99 percent of GDP in 2027. Assuming all these temporary policies were further extended in future years,* debt would reach the all-time record of 106 percent of GDP by 2027.

It doesn't have to be this way. Trillion-dollar deficits don't need to return next year, and debt doesn't need to reach record levels by the end of the decade, but to avoid this, policymakers will need to adopt the basic rule of stop digging. Our debt is already higher than any time since just after World War II. There's no need to make it even worse.

Update: 12/4/17. We updated the table after publication to show the total of $4 trillion, the sum of the $2.2 trillion potential cost of December legislation and the $1.8 trillion cost if all the temporary provisions are continued.

*This assumes temporary provisions in the Senate tax bill are made permanent, the discretionary sequester is repealed and caps are further increased by $10 billion per year through 2027, Obamacare tax provisions are permanently repealed, all extenders are made permanent, and CHIP is permanently reauthorized.