How High Are Federal Interest Payments?

This year, the federal government will spend $300 billion on interest payments on the national debt. This is the equivalent of nearly 9 percent of all federal revenue collection and over $2,400 per household. The federal government spends more on interest than on science, space, and technology; transportation; and education combined. The household share of federal interest is larger than average household spending on many typical expenditures, including gas, clothing, education, or personal care.

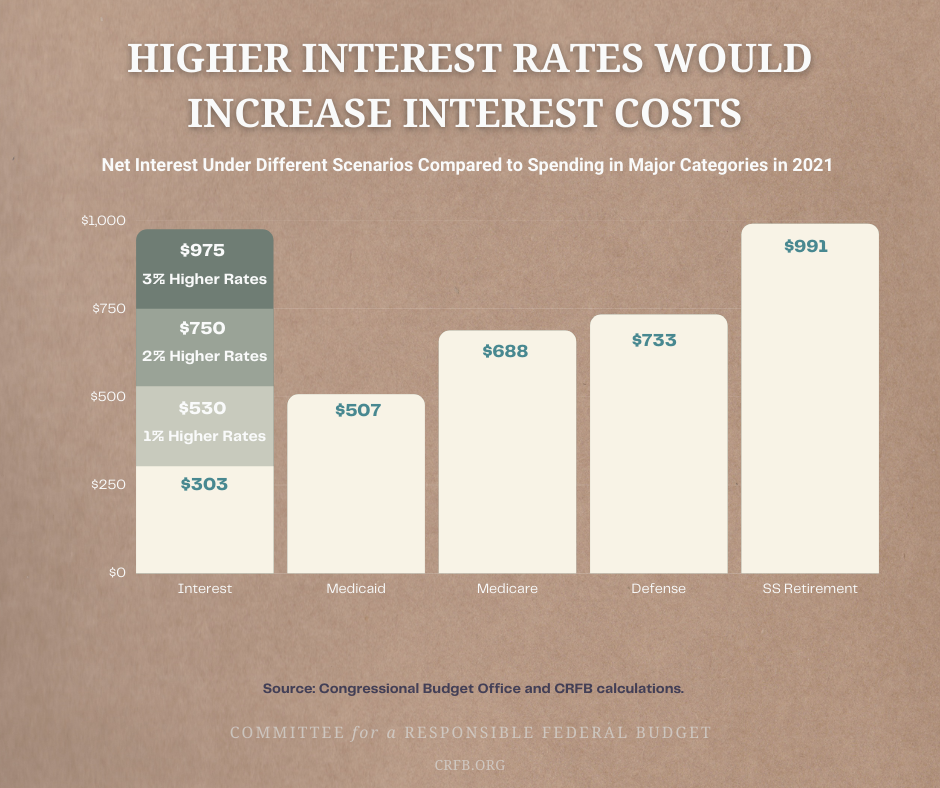

Despite historically low interest rates, this significant interest cost is the result of high levels of debt. This cost could be even worse if interest rates rise. Each one percent rise in the interest rate would increase FY 2021 interest spending by roughly $225 billion at today’s debt levels. Growing debt levels not only add to the likelihood of such increases, but also the cost and risk associated with them.

This brief puts these interest payments in context. Estimates are based on CBO’s February 2021 baseline and do not incorporate the effects of the American Rescue Plan.

How Much Does the Federal Government Spend on Interest?

Even with exceptionally low interest rates, the federal government is projected to spend just over $300 billion on net interest payments in fiscal year 2021. This amount is more than it will spend on food stamps and Social Security Disability Insurance combined. It is nearly twice what the federal government will spend on transportation infrastructure, over four times as much as it will spend on K-12 education, almost four times what it will spend on housing, and over eight times what it will spend on science, space, and technology.

Twitter

TwitterInterest Payments Equal a Large Share of Household Income

The roughly $300 billion spent on federal net interest payments in FY 2021 is equivalent to over $2,400 per household. That’s more than the typical household spends on major household expenditures, including household furnishings; gas; clothing; education; meat, eggs, and dairy; or personal care in a given year. Interest payments effectively consume more than half of the worker-side payroll tax paid by households and are almost twice as large as total payments received through federal excise taxes and customs duties.

Twitter

TwitterHigher Interest Rates Would Increase Interest Costs

As interest rates rise, the cost of debt service payments will grow. Today’s low interest rates are partially the result of the COVID-19 pandemic, economic fallout, and response (though also partially reflect a long-term trend), and are thus unlikely to last. For example, although the rate on the 10-year Treasury note fell from just below two percent at the beginning of 2020 to nearly 0.5 percent by August, it has since rebounded to around 1.5 percent. CBO projects it will continue growing to 3.3 percent by the end of the decade, though that projection comes with a high degree of uncertainty.

Higher interest rates will mean higher interest payments and deficits. For example, if interest rates were one percentage point higher than projected for all of 2021, interest costs would total $530 billion — more than the cost of Medicaid. If rates were two percentage points higher, interest costs would total $750 billion, which is more than the federal governments spends on defense or Medicare. And at three percentage points higher, interest costs would total $975 billion — almost as much as is spent on Social Security benefits. On a per-household basis, a one percentage point increase in the interest rate would increase costs by $1,805, to $4,210.

Twitter

TwitterWhile such a large interest rate hike is unlikely to occur in such a short period of time, it may very well occur over time. Rate increases would be more expensive if they took place further in the future, since higher debt increases their cost. The higher the federal debt, the more exposed the federal government is to interest rate risk.

Conclusion

While interest rates on the national debt are low historically speaking, the sheer amount of debt means that the federal government still spends billions of dollars on interest payments every year. These payments are larger than many federal government programs. Plus, because the debt we hold today will carry over into future years, there is considerable risk that higher potential future rates will result in interest payments that crowd out spending on even the largest government programs and priorities.

Given this risk, it would be prudent to address our long-term structural debt issues sooner rather than later. Once the U.S. recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, policymakers should work to adopt a combination of entitlement reforms, smart spending reductions, and revenue increases that will ultimately put debt and deficits on a more sustainable path.

Note: An earlier version of this paper erroneously listed Science, Space, and Tech expenditures as R&D spending. This paper has also been updated to clarify changes in interest rate are on a percentage point basis.