The Tax Break-Down: Tax Extenders

This is the sixteenth post in our blog series, The Tax Break-Down, which analyzes and review tax breaks under discussion as part of tax reform. Previously, we wrote about the Charitable Deduction, which lets itemizers deduct the amount they donate to charity. Read more posts in the Tax Break-Down here. This blog examines the provisions that expired at the end of 2013.

Among the unfinished business that Congress did not address in 2013 was a collection of over 50 tax provisions that expired at the end of the year. Most of these "tax extenders" have been extended before, usually a year or two at a time. The perennial use of these extenders creates unnecessary uncertainty for individuals and business, obscures their true budgetary cost, and will likely push debt levels higher going forward. If Congress chooses to extend any of these provisions, they should be fully offset by savings elsewhere in the budget. Ideally, Congress would resolve the quasi-permanent status of these extenders as part of tax reform, evaluating each one and either making it permanent or letting it expire.

The provisions that expired in 2013 contain a hodgepodge of different types of tax breaks. Some are not normal tax extenders but meant to be temporary stimulus efforts, such as the ability of underwater homeowners to write off forgiven mortgage debt or bonus depreciation allowing business to write off new capital spending. Others are relatively longstanding elements of the tax code, like a credit for research or a deduction for teachers who spend their own money on school supplies. Some are broadly available, like a deduction for sales taxes paid, while some are narrow tax breaks for specific industries, such as the wind production credit or special depreciation for NASCAR tracks and racehorses. The appendix below describes the biggest and most often discussed extenders.

The last time the extenders expired was at the end of 2011, but they were not addressed until the fiscal cliff legislation at the beginning of 2013. At that time, several provisions were allowed to expire, including ethanol credits and energy grants, and other provisions like bonus depreciation were scaled back. As a result, the total size of the extenders package decreased by about one-third. The others were extended for one year (and retroactively for 2012). Retroactive extensions up to a year are possible because most individuals do not file their tax returns until the next year. However, some provisions that are taken throughout the year (like the monthly transit benefit taken out of paychecks) are difficult to claim retroactively.

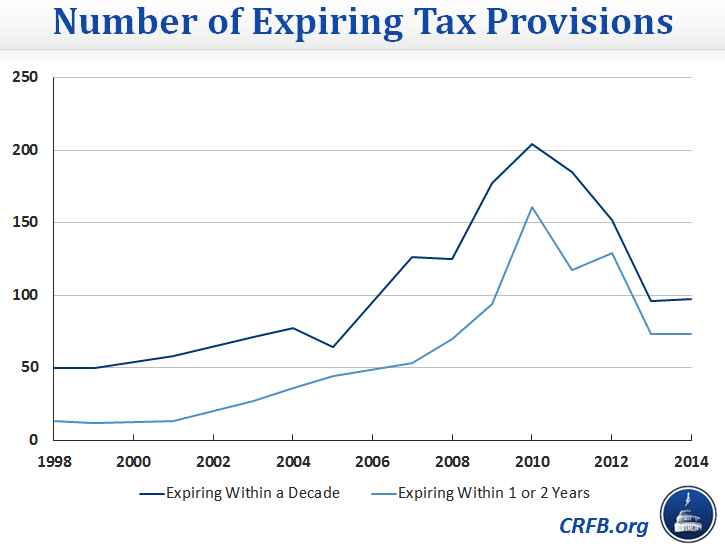

Over the last 15 years, Congress has increasingly relied upon temporary provisions, with the number of expiring provisions annually quadrupling between 1998 and 2010. The number decreased after 2010, when the 2001/2003 tax cuts were first scheduled to expire.

Source: Joint Committee on Taxation documents, American Enterprise Institute

What Are The Drawbacks of Having Provisions That Expire?

In theory, there may be good reasons to enact a tax provision on a temporary basis. For instance, a provision could be enacted briefly to measure its effectiveness. A short-term provision may be appropriate in response to a natural disaster or economic downturn. Unfortunately, most extenders are not reviewed regularly and are often extended one year at a time simply to hide their budgetary cost.

Many critics argue that tax extenders are not meaningfully evaluated, create unnecessary uncertainty, and are less effective than a permanent provision. Although temporary provisions theoretically force Congress to look at the costs and benefits of each measure before deciding to extend it, critics argue that “no real systematic review ever occurs,” since the extenders are grouped and passed as a “package of unrelated temporary tax benefits.” Further, the uncertainty whether a provision will be extended diminishes its usefulness as an incentive. Retroactive extensions complicate financial accounting and are much less effective at incentivizing behavior, mostly providing a windfall to reward behavior that has already occurred. In several cases, such as the tax credit for research and experimentation, the uncertainty makes it difficult for companies to engage in long-term planning.

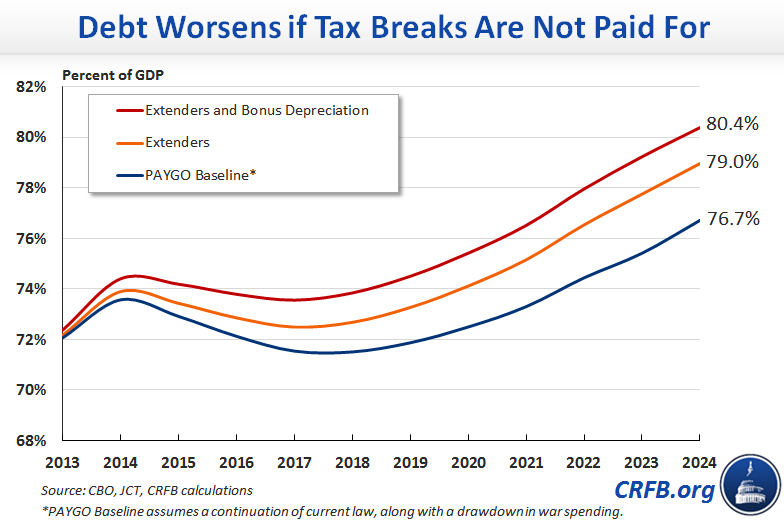

Further, classifying these quasi-permanent provisions as tax extenders distorts the budget picture. Under the law used to make budget projections, the Congressional Budget Office assumes that temporary tax provisions are just that—temporary. However, Congress almost always extends these provisions by adding to the deficit. (Past years have also included the expensive AMT patch, which has since been enacted permanently.) The extensions therefore make the budget picture worse than CBO’s official budget projections shows. If Congress extends these provisions without paying for them, the debt at the end of the decade would be nearly 4 percent of GDP larger.

How Much Do They Cost?

If all of the expired tax provisions were extended for one year, it would cost approximately $42 billion over the next ten years. The vast majority of the money, about 80 percent, is for business or energy provisions. Not all of these extenders are equally sized; most of them cost under a billion dollars. Five provisions, less than a tenth of them, make up three-fifths of the total cost of a one-year extension.

If the provisions were extended for two years (retroactively for 2014 and forward for 2015), the bill would cost about $85 billion. Permanently extending the provisions would cost approximately $450 billion through 2024, or $700 billion including bonus depreciation. Business extenders make up two-thirds of the total cost.

| Cost of Extending the Tax Extenders (2014-2024) | |||

| Policy | One-Year Extension | Two-Year Extension | Permanent Extension |

| Individual Tax Provisions | |||

| Sales Tax Deduction | $3 billion | $6 billion | $35 billion |

| Mortgage Forgiveness Exclusion | $3 billion | $5 billion | $15 billion |

| Charitable Donations of IRAs | $0.4 billion | $2 billion | $8 billion |

| Tuition and Fees Deduction | $0.3 billion | $0.6 billion | $2 billion |

| Other individual tax provisions | $1 billion | $3 billion | ~ $20 billion |

| Total, All Individual Provisions | $8 billion | $17 billion | ~ $80 billion |

| Business Tax Provisions | |||

| Research and Experimentation Tax Credit | $8 billion | $15 billion | $80 billion |

| Active Financing Income | $5 billion | $10 billion | $60 billion |

| Section 179 Expensing | $1 billion | $3 billion | $70 billion |

| Other Business Tax Provisions | $9 billion | ~$20 billion | ~ $80 billion |

| Total, All Business Provisions | $23 billion | $50 billion | ~ $290 billion |

| Energy Tax Provisions | |||

| Renewable Energy Production Tax Credit | $6 billion | $13 billion | $30 billion |

| Biodiesel Blending Credits | $1 billion | $3 billion | $20 billion |

| Other Energy Tax Provisions | $2 billion | $2 billion | ~ $30 billion |

| Total, All Energy Provisions | $9 billion | $18 billion | ~ $80 billion |

| Grand Total, Traditional Tax Extenders | $40 billion | $84 billion | ~ $450 billion |

| Bonus Depreciation | $1.5 billion | $3 billion | $250 billion |

| Grand Total, All Expired Provisions | $42 billion | $87 billion | ~ $700 billion |

Source: CBO Expiring Tax Provisions, and JCT revenue estimate from the EXPIRE Act, and the House's one-year extension. Totals do not add due to rounding.

What Have Other Plans Done?

Various tax reform plans make different decisions about which extenders to extend and which to let expire. For instance, the Domenici-Rivlin plan keeps an extender dealing with the international income of financial firms while eliminating most other tax breaks. The Center for American Progress would extend the research & experimentation credit permanently, while assuming the rest expire or are offset with other revenue. And the Simpson-Bowles plan assumes most of the extenders are allowed to expire (though only a few are mentioned explicitly).

The President's Budget permanently extended some provisions while remaining silent on many others. Among the extended provisions were the research & experimentation tax credit, a credit for renewable energy production, incentives for energy efficiency, and certain hiring incentives. Encouragingly, the President paid for all the extensions he included in the budget. The provisions he did not mention are implicitly assumed to either expire or be paid for in the context of business tax reform.

Ways & Means Chairman Dave Camp's tax reform draft makes a responsible choice to evaluate each of the extenders and pay for the ones it retains. The draft repeals dozens of extenders, but permanently extends a modified research credit and a write-off for small businesses making capital investments, as well as several of the smaller provisions. The few provisions that he temporarily extends persist for several years. A provision allowing financial firms to defer taxation on overseas income continues until 2019, when a lower corporate rate takes effect. The renewable energy production tax credit is reduced, but continues until 2024.

What Happens Now?

Though the tax extenders have been expired for over three months, Congress can restore them retroactively through at least the end of the year. Last year, the chairmen of the tax-writing committees did not address tax extenders, wanting to include them as part of an effort to reform the tax code. However, with tax reform efforts stalled, both the Senate Finance and House Ways & Means Committees seem prepared to address extenders on a separate track.

In late December, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid (D-NV) proposed a bill (which was never voted on) that would have extended all the provisions en masse, including the costly bonus depreciation, without paying for any of them. At the time, we called it an irresponsible tax extender package, and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities also stated the bill should be fully paid for.

More recently, new Senate Finance Chairman Ron Wyden (D-OR) has suggested that he would address these provisions "sooner rather than later," and is expected to consider the extenders as early as next week. While Wyden has not yet detailed his specific approach, we expect that most but not all expired provisions will be included in the initial package. Chairman Wyden has spoken favorably about the need to extend renewable energy provisions. Meanwhile, House Ways & Means Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) is proposing to move forward on permanently extending certain provisions as “incremental progress towards full reform.”

The tax extenders are one of the few pieces of legislation that Congress is expected to consider in 2014. It will be an important test of fiscal responsibility to see which tax preferences are extended and whether the costs are offset or if the provisions are added to the nation's credit card.

Where Can I Read More?

- See the appendix below for a description of the biggest and most often discussed extenders.

- Congressional Research Service - Tax Provisions Expiring in 2013 ("Tax Extenders")

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget - Tax Extenders: PAYGO or No Go

- Tax Policy Center - Testimony Before the House Ways & Means Committee

- Center on Budget and Policy Priorities - Paying for Tax Extenders Would Shrink Projected Increase in Debt Ratio by One-Third

- Bipartisan Policy Center - Tax Extenders Should be Permanent and Paid For

- American Enterprise Institute - Framework for Evaluating Tax Extenders

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget - Camp Makes Responsible Choices on Tax Extenders

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget - Paying the Costs of Bonus Depreciation

- Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget - Bonus Depreciation Has Cost $220 Billion Since 2008

- Rosanne Altshuler - Testimony Before The Senate Finance Committee

- Calvin Johnson - Evaluation of Specific Tax Extenders

* * * * *

Policymakers should take a careful look at each and every expiring provision – preferably as part of tax reform – rather than simply rubberstamping the continuation of all the extenders. Many of the provisions would not pass a cost-benefit analysis and should be reformed, phased out, or allowed to expire; other provisions may indeed be merited and should be made permanent; and there may even be some provisions where a temporary extension is warranted. In any case, whatever is continued should be fully offset with new revenue or spending cuts so as not to add to the national debt.

Appendix: Explanation of Select Extenders

Although there are over 50 provisions that expired at the end of 2013 (a full list is available here), below we describe some of the biggest, most popular, or most discussed provisions. Some of these provisions are the "normal tax extenders," provisions that have been enacted year after year and are almost a fixture in the tax code, while others are temporary stimulus measures passed in 2007 and 2008.

Tax Credits for Individuals

Sales Tax Deduction - One of the largest permanent tax breaks is the state and local tax deduction, which allows filers who itemize to deduct the amount paid in state or local income tax. However, people who live in states with no income tax cannot take advantage of this deduction. This provision created a deduction for sales tax states by allowing an individual to deduct either the amount they paid in sales tax or income tax since 2004.

Charitable Donations from an IRA - Under this provision created in 2006, retirees age 70.5 and older could donate up to $100,000 tax-free from their IRA each year to charity. Normally, the donation would be eligible for a charitable deduction, but this provision converts the deduction to a complete exclusion, which allows retirees to make their required IRA withdrawals without triggering a tax a Social Security benefits for retirees with income other than Social Security.

Tuition and Fees Deduction - This deduction, in place since 2001, allows filers with incomes less than $65,000 a year ($130,000 if filing jointly) to deduct up to $4,000 of tuition and fees paid for higher education. This provision was for filers who did not claim one of the other educational credits, and it phased out entirely for filers with incomes over $80,000 ($160,000 if filing jointly).

Educators' Out-of-Pocket Expenses - With this provision, originally enacted in 2002, teachers could deduct up to $250 of out-of-pocket expenses for classroom materials.

Parity for Commuter Transit Benefit - Before this provision expired, commuters could spend up to $245 a month of tax-free income for either transit or parking. After the expiration, the amount for transit has dropped to $130 a month, while the amount for parking rose with inflation to $250 a month, meaning that those who drive to work are now subsidized more than those who use public transit. The transit benefit originated in 1993 and became equal to the parking benefit in 2009.

Mortgage Debt Forgiveness - Normally, forgiven debt counts as taxable income. In response to the housing crisis, homeowners could exclude up to $2 million of canceled debt ($1 million if married filing separately) on their principal residence. The forgiveness must be directly related to a decline in the home’s value or the taxpayer’s financial condition. This provision was passed as temporary stimulus measure in 2007.

Tax Credits for Businesses

Research and Experimentation Credits - The R&E credit is one of the longest lasting tax extenders, having been extended 15 times since 1981. Currently, there are four separate credits. The main credit allows companies to claim a 14 percent credit for research expenses that are more than half of their three-year average, or 6 percent if the company had no research expenses for the past three years. The idea behind comparing a company's research spending with previous years is to only subsidize incremental research that would not already be undertaken by the company. This credit can also be carried forward 20 years.

Active Financing Exception for Subpart F - Normally, business income earned overseas is not taxed until it is repatriated to the United States, but "passive" income like rents, interest, and dividends are taxed immediately. The active financing exemption, in place since 1999, allows banks and financial institutions to treat the interest and dividends they receive like business income and not pay tax until they bring the money back to the United States.

Small Business Expensing (Section 179) - Generally, companies that make large capital purchases must deduct the cost over several years according to a set of depreciation schedules. Section 179 allows small business owners to immediately write off most depreciable assets, up to a certain limit. Section 179 has been allowed since 1958, but the limit has changed over time. In 2013, small businesses could write off up to $500,000 of purchases, an amount that phased out when total purchases exceeded $2.5 million. When this extender expired, total deductible expenses dropped to $25,000 (phasing out after $200,000 of purchases).

Special Depreciation Schedule for Motor Tracks - This provision, in place since 2004, allowed motor sport complexes to be depreciated over seven years, the same as amusement parks. Without this extender, these structures would be written off over 39 years, like most other buildings.

Special Depreciation Schedule for Racehorses - Without this extender, racehorses had different depreciation schedules depending when they started training: seven years if they started training before age two and three years otherwise. Under this tax provision, all racehorses have been depreciated over three years since 2009.

Immediate Expensing for Film & Movie Production - Since 2004, movie production studios had been able to deduct up to $15 million in expenses if more than 75 percent of the production occurred in the United States, or up to $20 million if produced in a low-income community.

Bonus Depreciation - Bonus depreciation (different from permanent accelerated depreciation) allows companies to immediately write off a certain percentage of their purchases. It is not one of the normal tax extenders, but has been enacted frequently as a stimulus measure, most recently as part of the 2008 Economic Stimulus Act, when it was reinstated at a level of 50 percent. It was increased to 100 percent (also known as immediate expensing) in 2010, and reduced again to 50 percent for 2012 and 2013. Because bonus depreciation is largely a timing shift, a one year extension would have substantial immediate costs that would be largely recovered over time – though a permanent extension would be quite costly.

Tax Credits for Energy

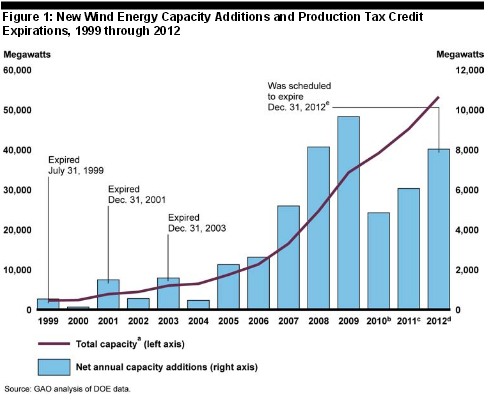

Renewable Energy Production Tax Credit - The federal renewable electricity production tax credit has been in place since 1992, but it has sometimes lapsed and been later extended. Sellers of renewable energy can claim a credit for every kilowatt-hour of energy produced. The most used is for wind energy, which receives a credit of 2.3¢/kWh. The credit has been partially responsible for the rise of new wind energy in the United States, as illustrated by the reductions in construction when the credit lapsed in 2000, 2002, and 2004. Former Senate Finance Chairman Baucus recently released a tax reform discussion draft focused on energy policy which would extend this credit, make it available to all types of clean energy, and phase out once the average unit of electricity is 25% cleaner than it is today.

Biodiesel Blending Credits - There are a number of different biodiesel credits, depending on whether the fuel is sold pure or blended, and whether it is made by a small producer. Generally, this provision provided $1.00 per gallon of pure biodiesel (or other renewable diesel fuels). These biodiesel credits have been in place since 2003 and 2005.

Energy Efficiency Credits - Several different energy efficiency credits expired, including a $2,000 credit for contractors building an energy-efficient home and a credit for each energy-efficient appliance manufactured. Some of these credits had existed since 2007, but many were created or expanded in 2009.

Update 12/2/2014 & 12/15/2014: We've updated the cost estimates in this blog for the most recent costs of a 1-year, 2-year, and 10-year extension, to reflect more recent estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation.