President Trump's Infrastructure Proposals, Explained

One of the key priorities for the White House has been infrastructure, with last week declared "infrastructure week" and President Trump unveiling more details about the proposals from his Fiscal Year (FY) 2018 budget as part of it. Below, we take a look at what we know about the President's infrastructure policies from his budget and what they intend to do.

Privatizing Air Traffic Control

The Administration kicked off infrastructure week with a speech on air traffic control, outlining principles for moving most air traffic operations from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to a new private, non-profit entity tasked with conducting most of the non-safety aspects of air traffic control. Those principles include:

- Creating the new entity to be separate from the federal government

- Maintaining the federal government's role in safety and regulation of U.S. airspace

- Enabling the new entity to be accountable to an independent board of directors, filled at first by an arrangement of air traffic stakeholders

- Allowing for the new entity to enact the fee structure necessary to fund its operations

The White House proposal often cites its similarities to the Aviation Innovation, Reform and Reauthorization Act of 2016, introduced last Congress by House Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Chairman Bill Shuster (R-PA).

Currently, the FAA is charged with directing airplanes and other aircraft throughout the United States, including both the aviation safety standards set for U.S. airspace and the day-to-day guidance for proper air travel. Under the Trump Administration's proposal, the FAA would continue to regulate safety standards but relinquish most air traffic control operations to the new corporation. The Administration argues that this would allow air traffic control to be more responsive to new technologies (like consumer drones and commercial spacecraft), encourage efficiency to the benefit of aviation stakeholders, and reduce the user fees imposed to pay for air traffic control operations.

Privatization would take federal air traffic control spending and revenues off the books, putting both in the hands of a new non-profit. However, because current taxes are greater than spending, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) estimates the result would be $70 billion less in spending and $116 billion less in revenue over a decade – with a resulting $46 billion increase in the deficit.

$200 Billion of Infrastructure Investment to Help Spur $1 Trillion in Total Investment

During the campaign, the President called for a plan to generate $1 trillion of new infrastructure spending. The budget includes a $200 billion placeholder to help achieve this goal. In theory, this $200 billion – along with various regulatory reforms – would be leveraged into $1 trillion of federal, state, local, and private investment.

The $200 billion would be used for a variety of purposes, including direct spending, expansion of Private Activity Bonds (PABs), and helping to foster public-private partnerships. It is also possible some of the funds could be used for an infrastructure bank and/or some type of infrastructure tax credit as proposed by then-Trump campaign advisors Wilbur Ross and Peter Navarro during the campaign. The White House also called for promoting infrastructure by loosening regulations on interstate highways – including a holdover Obama proposal to allow more toll roads – and accelerating approval of new permits and projects.

The budget assumes most of the $200 billion of new federal infrastructure spending would take place between 2019 and 2022, and all spending would be complete before 2027.

Assuming Highway Trust Fund Spending Aligns with Revenue

Currently, CBO's baseline for highway spending assumes that spending continues at authorized levels, and then grows with inflation after the highway bill expires, despite the fact that the Highway Trust Fund (HTF) is projected to run out of funds in 2021. In reality, there remains a large gap between highway spending and dedicated revenue (mainly the gas tax) used to fund it. This gap must be closed.

The President's budget assumes that highway spending will be reduced to match dedicated revenues. As a result, highway spending will fall $95 billion over a decade, including $20 billion in 2027.

This approach is fiscally responsible and an alternative to raising the gas tax that would ensure highway spending and revenues remain in line. In fact, we suggested this approach – along with a significant gas tax increase to update it for inflation – in The Road to Sustainable Highway Spending. However, this proposal does run somewhat counter to the goal of increasing overall infrastructure spending.

Other Infrastructure Proposals

Apart from the main proposals above, which mostly address mandatory spending, the President's budget calls for discretionary cuts to the Transportation Department as first noted in the "skinny" budget. These cuts include eliminating the Essential Air Service, eliminating the TIGER grant program for infrastructure projects, halting new grants from the Capital Improvement Grant program, and discontinuing federal support for long-distance Amtrak travel. Taken together, these cuts would reduce infrastructure funding by $2.2 billion in 2018, suggesting reductions of about $20 to $25 billion over a decade.

The President's Budget's Net Effect on Infrastructure

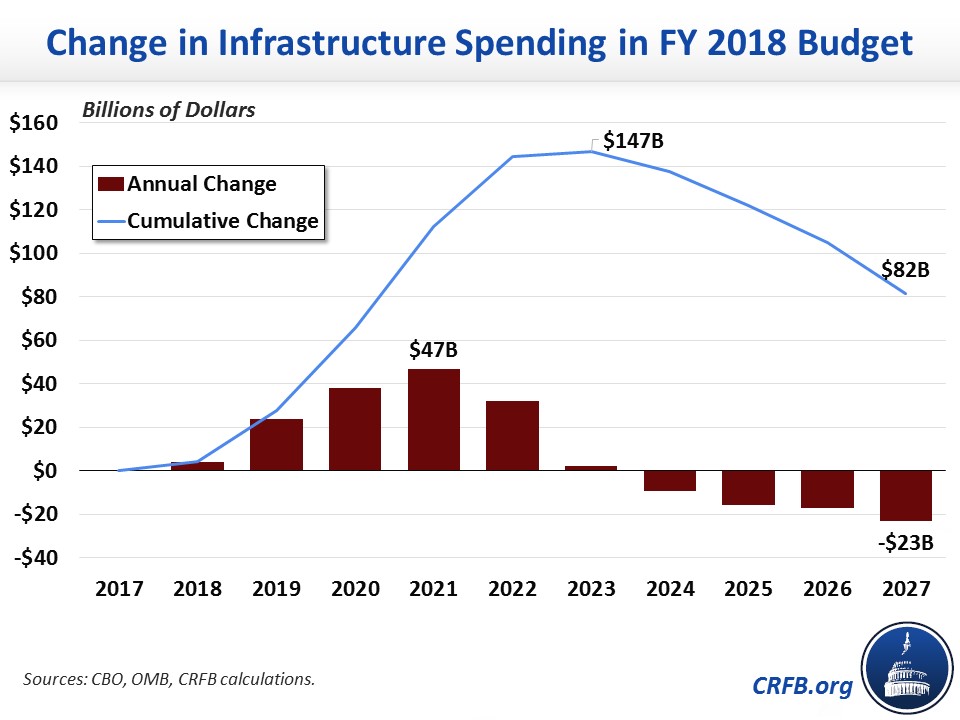

Although President Trump proposes $200 billion of additional gross infrastructure spending, on net his budget would increase infrastructure by closer to $80 billion. New infrastructure spending would reach nearly $150 billion by 2022 but would fall $65 billion between 2023 and 2027 as a result of highway funding cuts (including almost $25 billion in 2027).

Although the budget would reduce federal infrastructure spending in later years, these changes (assuming they are paid for with other cuts in the budget) would likely be modestly pro-growth within the budget window – particularly if they are successful in leveraging state, local, and private financing as intended. In fact, as we showed recently, front-loaded infrastructure spending may be slightly more pro-growth than sustained infrastructure spending, on a per dollar basis, because of today's low interest rates.

Importantly, however, the economic gains of new spending are likely to be quite small, and they may even disappear or reverse if new infrastructure spending is not fully paid for. The Congressional Budget Office has shown that fully offset infrastructure spending is more pro-growth than deficit-financed infrastructure.

As policymakers consider the President's proposals, they should therefore ensure new spending is fully paid for. In the past, we've written about a large number of ideas to pay for infrastructure spending within and fully fund the HTF. Ideas fall in the following four categories: