How Much COVID Relief Money Is Left?

Note: Data updates on February 3, 2021 reduce the difference between legislative amount allowed and committed/disbursed from $1.3 trillion to $1.1 trillion. Most of the additional disbursal is from the end-of-year Response and Relief Act.

Our newly updated COVID Money Tracker tool estimates that Congress has allocated $4 trillion of gross fiscal support, of which at least $2.7 trillion (over two-thirds) has been committed or disbursed as of January 22. But the question of how much relief money remains is a complicated one.

Subtracting the amounts allowed from the amount committed or disbursed yields a figure of $1.3 trillion — but that does not mean that $1.3 trillion is sitting in budget accounts waiting to be allocated. Much of it is already allocated or scheduled to be spent, and a small portion will never be spent.

Nearly 60 percent of this $1.3 trillion comes from the Response & Relief Act enacted one month ago — these funds will take some time to disburse and even more time to appear in the data. Another fifth of the funds come from Medicaid spending that is expected to pay out over several years as well as from available, but untapped, Economic Injury Disaster Loans.

The remaining money comes from a combination of policies that are expected to pay out over time, haven’t yet been allocated, or for which data is not currently available. Some of the funds may never be spent, especially in the case of entitlement or revenue changes that end up costing less than expected. For example, the 13-week extension of unemployment benefits in the CARES Act may end up costing less than previously estimated due to lower long-term unemployment.

Divided by legislation, about $775 billion (59 percent) of the $1.3 trillion difference between amount allowed and committed/disbursed come from the recently-passed Response and Relief Act – and the actual figure may be lower since money is being disbursed very quickly (for example, our current dataset does not yet reflect Paycheck Protection Program loan data that was released yesterday) and data sometimes is updated with a lag. Another $220 billion (17 percent) comes from the Paycheck Protection Program and Health Care Enhancement Act (PPPHCE), $195 billion (15 percent) from the CARES Act, and $125 billion (10 percent) from the Families First Act.

Over the course of our data update this weekend there was a temporary coding error in our tracker that made it appear the difference between allowed and committed funds was $1.8 trillion if you filtered by legislation and then added the amounts from each piece of legislation together.1

Our data shows that at least a fifth of funds from the Response & Relief Act have already been committed or spent as of our last update, and the actual number is likely to be higher based on the funds that have been committed in the last week or have been committed but not yet reported.

Meanwhile, over 80 percent of allowed funding from prior bills has been committed or disbursed — around half of the remaining funds are related to ongoing Medicaid spending and available Economic Injury Disaster Loans.

Excluding the recently-passed Response & Relief Act, about $220 billion (17 percent) of the remaining funds are policies that are meant to pay out over time, $235 billion (18 percent) are policies that the funding has simply not been disbursed yet, and $90 billion (7 percent) are from policies where little or no data is available.

As an example of policies that pay out over time, higher Medicaid matching payments to states will have ongoing costs so long as the public health emergency remains, so it will likely disburse over a multi-year period. We estimate the federal government has disbursed $55 billion in additional Medicaid funds so far, while CBO estimates they will ultimately disburse $165 billion. As an example of money yet to be disbursed, there are approximately $170 billion of EIDL loans available — out of $366 billion — for small businesses to apply for.

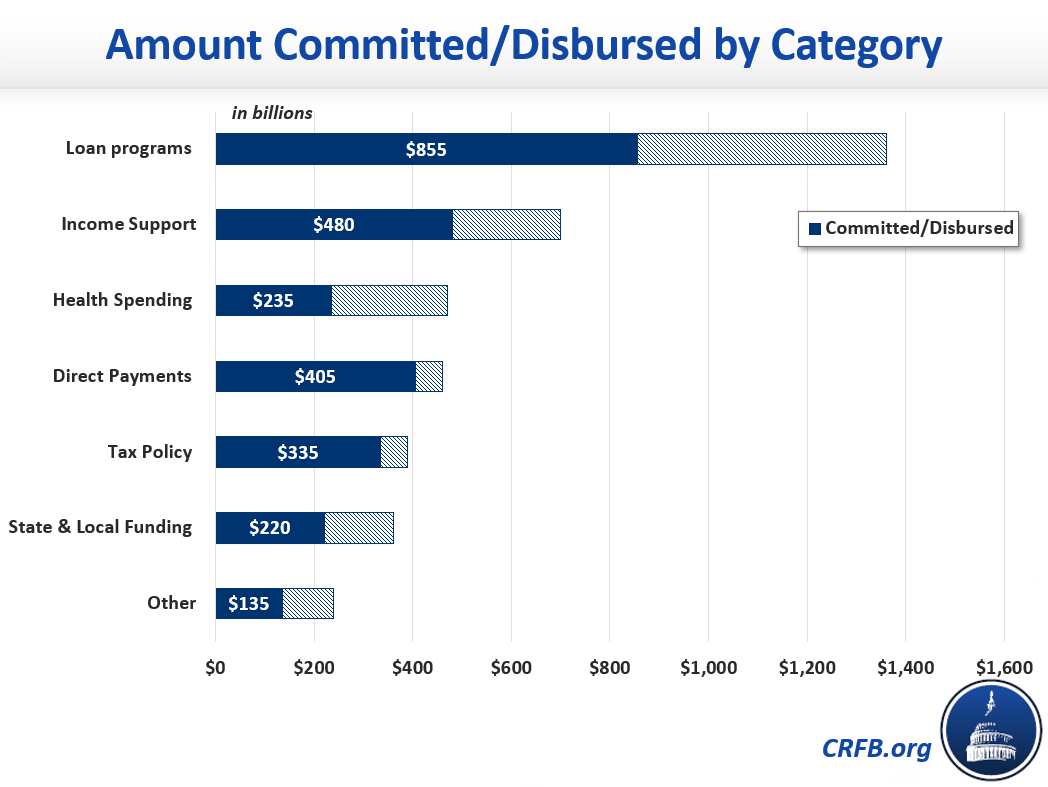

A final way to look at the funds remaining is by support category. We estimate the vast majority of allowed direct payments (recovery rebates) and 2020 tax breaks has been disbursed or committed, along with most income support spending such as unemployment benefits. More will be claimed as people file their 2020 tax returns and are paid expanded unemployment benefits into March.

A smaller share of health care and loan program spending is out the door, though this may change in the coming weeks as more businesses take a second-draw Paycheck Protection Program loan and the Biden Administration executes its vaccine and COVID response strategy.

Our figures above measure the gross fiscal support, not the net cost to the federal government. Loan programs and tax deferrals get fully or partially repaid and have a larger upfront costs than their expected deficit impact. For instance, it will only cost the federal government a maximum of $50 billion to offer an estimated $365 billion of EIDL loans.

On a deficit impact basis, which charges loans based on their subsidy cost, at least $2.45 trillion has been committed or disbursed so far, out of a net expected cost of $3.4 trillion.

It is also important to point out that a small portion of allowed COVID relief money may never be spent, though CBO estimates suggest that over 90 percent of the spending provisions and more than all the revenue provisions will be disbursed by the end of the fiscal year.2

As funds continue to be distributed and data is updated, we will continue to track all of the federal COVID relief response at www.COVIDMoneyTracker.org.

1 A small amount of undisbursed funds — about $20 billion — are tagged with multiple legislation. Vaccines, for instance, have been funded through multiple bills and it is impossible to identify which funding was spent. The Provider Relief Fund has also been funded through two different pieces of legislation, and our website tags this money as the original funding legislation — the CARES Act — overcounting the allowed amount of this bill by $75 billion and undercounting the PPPHCE Act by $75 billion. As a result, there will be a small differences between adding each individual piece of legislation and viewing the aggregated total.

2 In several cases, more than 100 percent of the ultimate revenue cost can be disbursed to the economy in the near-term. Several provisions, such as those affecting business losses and charitable deductions encourage taxpayers to claim benefits upfront at the expense of higher taxes in later years. The proposals cost in the short-term, but raise money in later years. Conversely, there are several tax provisions which were utilized much less than originally anticipated, so JCT’s original estimates vastly overstated the cost.