Five Gimmicks Only Budget Wonks Get

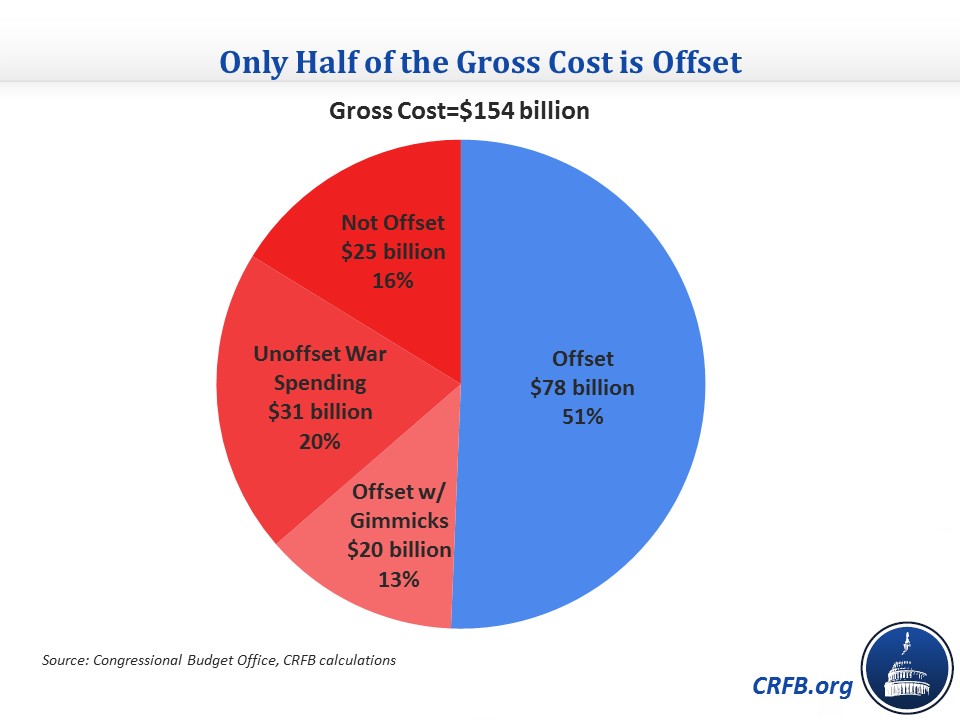

The Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015, signed into law earlier this week, is fully offset over the next ten years, according to the scoring conventions of the Congressional Budget Office. However, we showed that the deal truly offsets only half its cost if you include interest costs and exclude the savings from several budgetary gimmicks. This blog explains the five gimmicks used in the deal.

Five Gimmicks

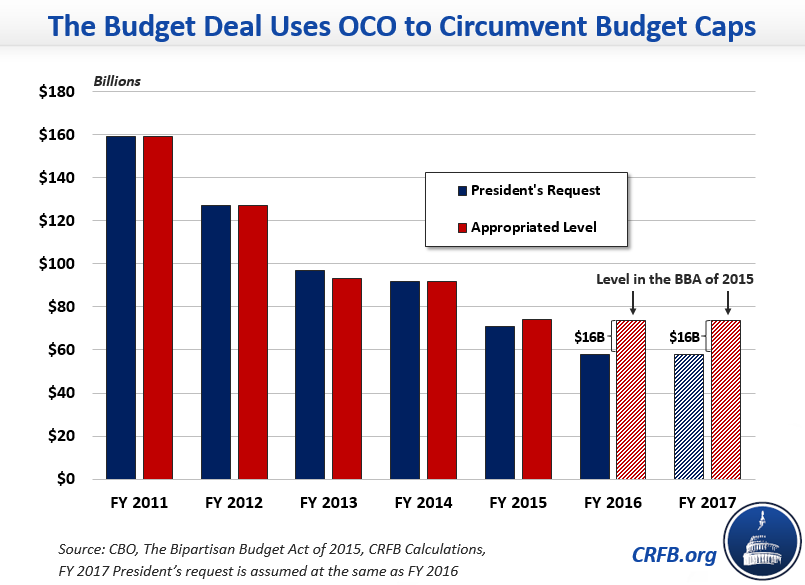

War spending: About $31 billion of the spending increases come from war spending, known as "overseas contingency operations" (OCO). This money is not subject to the normal caps on defense and non-defense spending, so using OCO is a way to increase spending and circumvent the caps. We describe this gimmick in more detail here.

The deal provides $74 billion for OCO spending, which is $16 billion higher than the President's request of $58 billion. The same amount is allocated for this fiscal year (FY2016) and FY2017, meaning that the spending increase for both years over the President's FY2016 request is $31 billion -- and it is quite possible the FY2017 spending increase will be higher if the President's request for that year is lower than this year's. This funding establishes a dangerous precedent that the OCO category is explicitly a slush fund to get around the discretionary spending caps. In the past, lawmakers have used OCO on the margins for this purpose, but not as explicit sequester relief.

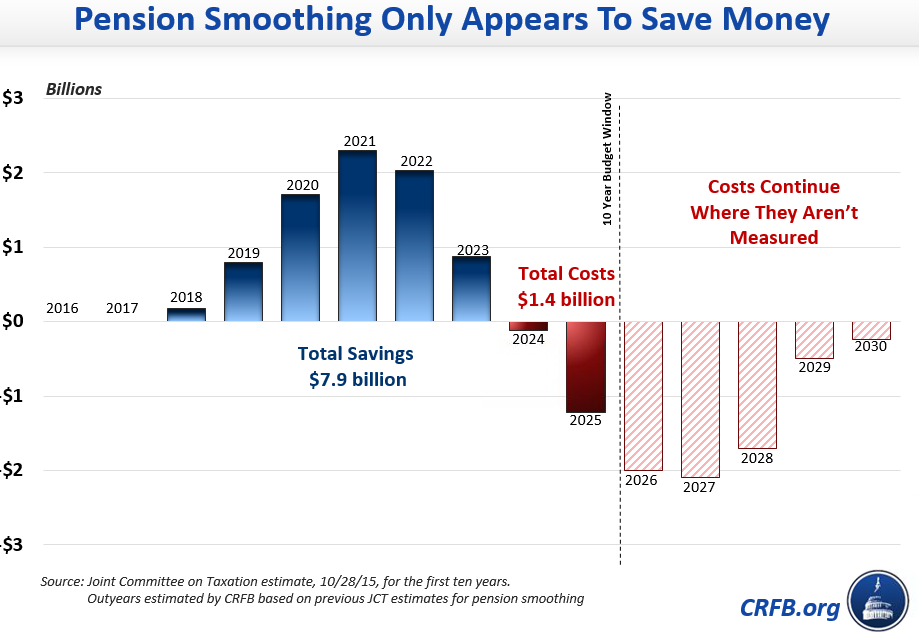

Pension smoothing. A much-derided gimmick called “pension smoothing” has returned from 2012 and 2014 transportation legislation. This provision temporarily reduces the amount that companies must contribute to their pensions, which increases profits and therefore taxes. However, pension contributions are increased later to make up the difference (which decreases tax revenue), so the net effect is close to zero. The provision is a timing gimmick that only appears to raise revenue because not all of the revenue losses appear inside the budget window. For more, see our explanation and a round-up of think tanks and editorial boards that are opposed to the budget gimmick.

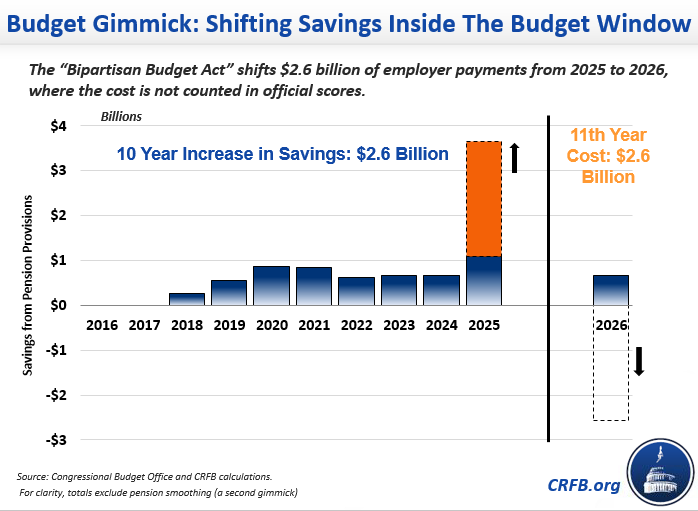

Timing Shifts: The agreement changes the date of premium payments that employers would normally make to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PBGC) from October 15 to September 15 starting in 2025. This produces no actual savings but causes one month’s payments to shift from FY 2026 (outside the ten-year budget window) to FY 2025 (inside the budget window). The shift creates on-paper “savings” of about $2.6 billion but creates an equal cost in 2026 – where it is not counted. A similar trick was used in previous Medicare “doc fixes” to create phony savings.

SSDI Double-Counting: The agreement includes about $4 billion of Social Security savings, a modest but positive move for the program’s finances. However, these savings, which ultimately go to the program's trust funds and allow higher spending on disability insurance than would be the case under current law, are also counted to offset the sequester relief. The money can only be counted once. Since the $4 billion will remain in the trust funds (improving solvency), it should have not been counted as an offset. We describe Social Security Changes in the Budget Deal in more detail in another blog.

Counting Savings That Won't Be Allowed to Take Effect: The agreement includes about $3 billion of crop insurance savings by reducing the rate of return that crop insurance companies receive when selling subsidized insurance plans. We described this provision in more detail in Lawmakers Promise to Repeal Crop Insurance Reforms. Yet lawmakers have already vowed to undo these savings. If lawmakers had no intention of letting the savings go into effect, they should not have used it as an offset. When these savings are repealed, they should be replaced with an equal or greater amount of real savings elsewhere, not additional budget gimmicks.

And One Not-Quite Gimmick

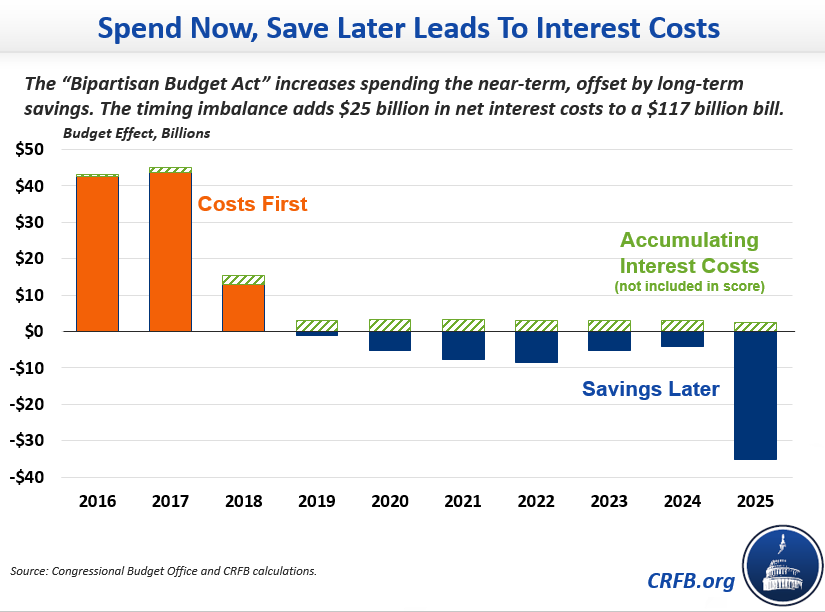

Backloaded One-Time Payfors: The bill includes several sources of one-time savings, such as $14 billion from extending the mandatory sequester to 2025 and $5 billion from selling oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Both take place several years in the future. Although it is generally acceptable to pay for one-time costs (like sequester relief) with these one-time savings, there are additional interest costs when spending in the first year is not offset until later years. We showed this effect in Everything You Need to Know About Budget Gimmicks.