Brookings Rethinks...New Revenue Sources

Throughout the week we have been breaking down the new report from the Brookings Institution's Hamilton Project, "15 Ways to Rethink the Federal Budget." Proposals have included reforms to the military, tax expenditures, Medicare, Social Security Disability Insurance, and Natural Disaster Assistance, Transportation, Visas & Housing Finance. In our final blog we take a look at two proposals to create new taxes -- a value-added tax and a carbon tax, that unlike our income and corporate tax systems, would tax behavior that economists generally do not want to promote and create better incentives.

Value-Added Tax

William Gale of the Brookings Institution and Benjamin Harris propose instituting a 5 percent broad-based value-added tax (VAT) in their proposal, "Creating an American Value-Added Tax." VATs are in place in 150 countries, including every OECD country besides the U.S. Economically, the VAT is like a sales tax in that it taxes consumption and therefore incentives saving. However, unlike the sales tax, which is only applied at the final point of sales, the VAT is collected at every stage of production, making it easier to administer and increasing compliance. A VAT would be applied to imports but not on exports, allowing for neutral treatment.

However, the VAT has been criticized on two fronts. The first is that it is regressive, since lower income households consume more of their income than wealthier households, and consumption is taxed at a flat rate regardless of income level. The other common reservation with VATs is the "low profile" of the VAT, being automatically build into the price of a good, that could allow governments to increase spending with less taxpayer awareness than with income taxes.

Gale and Harris attempt to solve these two problems. They propose to add a new 5 percent VAT that would tax all consumption apart from spending on charities, education, Medicare and Medicaid, and state and local government. However, to prevent making the tax code less progressive, they recommend that the VAT be paired with a cash payment of $450 per adult and $200 per child. This would be approximately equal to refunding the VAT tax for the first $26,000 of consumption for a two-parent, two-child household. To avoid disrupting the economic recovery, the VAT wouldn't go into effect until 2017, when the CBO projects the economy will return to trend. Even with the VAT implemented in 2017, it would still raise $1.6 trillion in revenue over the 2014-2023 period.

Gale and Harris argue that the VAT doesn't have to be invisible, citing the example of Canada requiring the VAT to be shown on each receipt (as sales taxes currently are in the U.S.). They also challenge the idea that a VAT would lead to lead to increasing government spending as the average VAT revenue has remained relatively constant among OECD countries since the 1980s. If the VAT were also accompanied by spending targets or long-term entitlement reforms, this could also prevent the government from becoming too reliant on the tax.

Carbon Tax

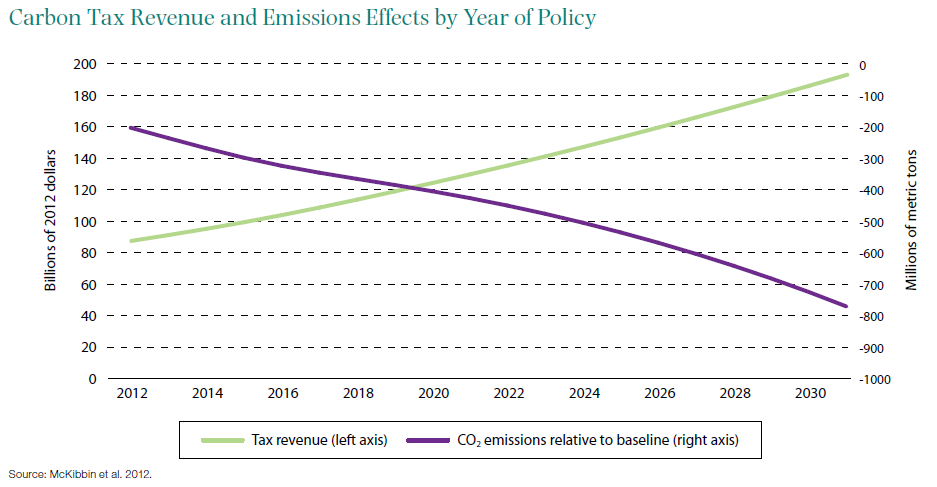

Just as most budget experts argue that the unsustainable budget deficit represents a great threat to our future, most climate scientists believe that climate change presents a similar threat. Adele Morris of the Brookings Institution argues in her proposal "The Many Benefits of a Carbon Tax" that there is an opportunity to address both at the same time. A carbon tax could raise new revenue for deficit reduction while also encouraging abatement of CO2 emissions.

Morris's proposal recommends a tax of $16 per ton of CO2 emmissions, increasing by inflation plus 4 percent. A carbon tax should ideally be priced at the social cost of carbon according to Morris, but the social cost is unknown. Still, the $16 tax falls within the range of U.S. government estimates. The tax is set to increase by 4 percent plus inflation to make it easier for businesses to plan and invest, while also discouraging quick extraction of fossil fuels to minimize tax liability. In total, this carbon tax would raise $1.1 trillion in revenue over the next ten years.

The U.S. has the world's highest statutory corporate rate and Morris proposes using some of the savings from the carbon tax to reduce that rate from 35 percent to 28 percent, at the cost of $800 billion over ten years. Morris would also offset the increase in the regressivity of the tax code by reserving 15 percent of revenue to benefit the poorest households. Finally, Morris recommends making the tax code simplier by eliminating many tax expenditures that promote renewable energy and fuels at a savings of $60 billion over ten years. Since the carbon tax would already provide strong incentives to abate emissions, these tax expenditures would become redundant. Altogether this proposal would reduce the deficit by $199 billion over the next ten years, and $815 billion over the next twenty.

*****

As we look to solve our unsustainable debt problem, it is clear that additional revenue will be needed. But increasing marginal income tax rates, which many economists believe would reduce incentives to work, is not neccessary. One approach might be to consider alternative taxes, like the ones above. Another approach, which we talk about frequently on The Bottom Line, would reduce the size of tax expenditures that litter our code, making it more complex, less efficient, and costing the federal government nearly $1.3 billion in forgone revenues according to the JCT. We can make reforms to make the tax code more favorable to growth and raise revenue for deficit reduction. We just need to take a look at the many ideas out there.