2019 Technical Panel Shows Social Security Could Be in Worse Shape Than We Thought

The Social Security Advisory Board's (SSAB) 2019 Technical Panel released its final report last week, projecting that under its suggested changes to assumptions and methods for evaluating the program's finances, the Social Security trust fund will be exhausted in 2033 – just 14 years from today, when today's youngest retirees turn 76 – two years sooner than projected by Social Security’s Trustees.

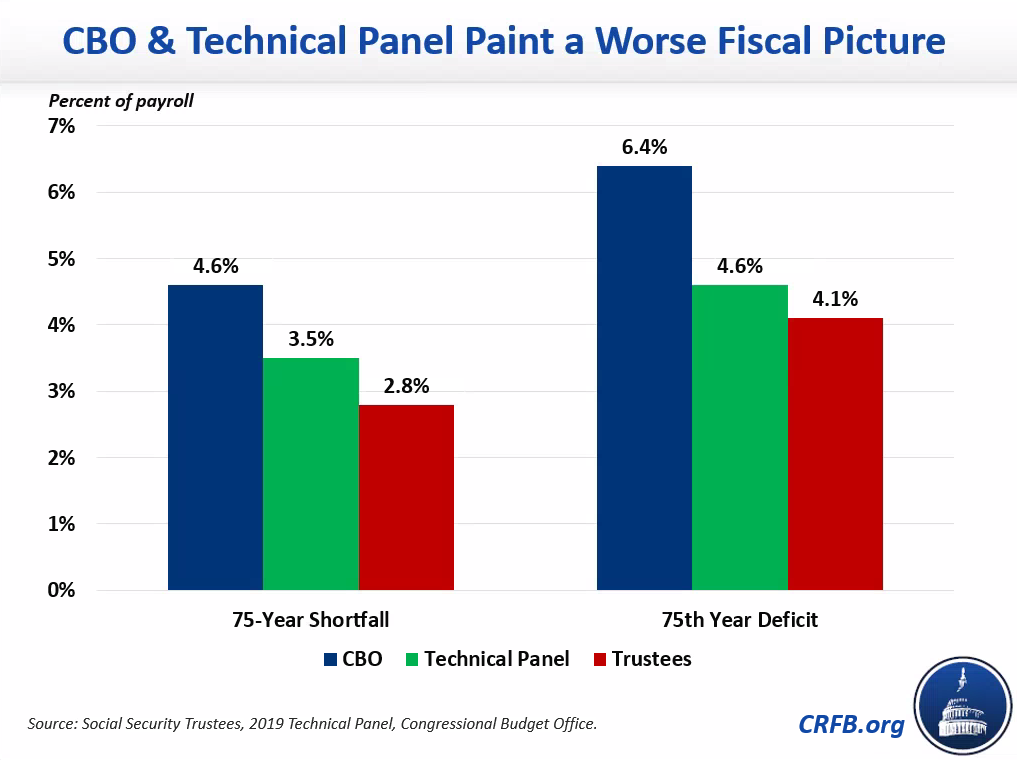

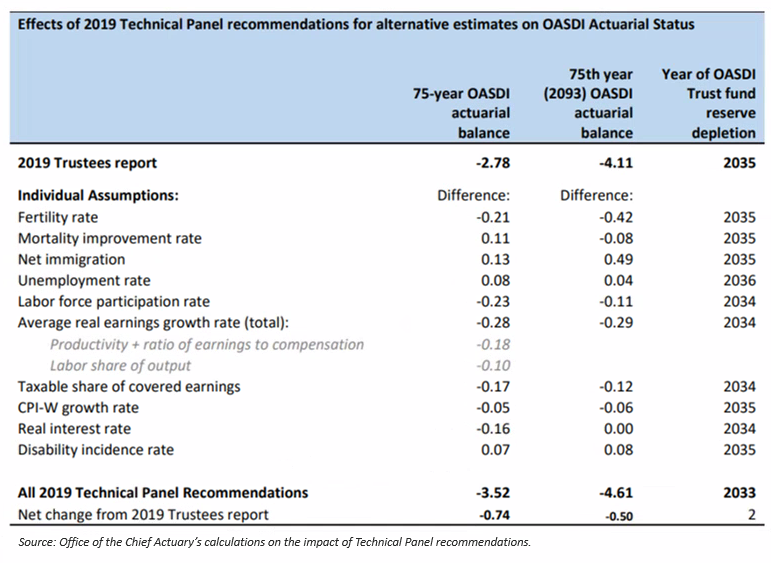

Every four years, SSAB assembles an expert panel of economists, actuaries, and experts to provide feedback on improving the Social Security Trustees’ report’s assessment of Social Security’s financial status. Using the Technical Panel's recommended assumptions paints an even worse picture of this year's report, with trust fund exhaustion in 2033, an actuarial deficit of 3.52 percent of payroll, and a 75th year deficit of 4.61 percent of payroll. In comparison, the 2019 Social Security Trustees' Report assesses an exhaustion date of 2035, a 75-year shortfall to equal 2.78 percent of payroll, and a 75th year deficit of 4.11 percent of payroll, while the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO) 2019 Long-Term Budget Outlook projects 2032, 4.6 percent of payroll, and 6.4 percent of payroll, respectively.

All three estimates show that the program's large structural deficit is not only urgent to fix soon, but it is also growing over time.

As we’ve talked about before, the assumptions and methods underlying organizations’ projections of Social Security’s financial health are crucial in producing the results. The Technical Panel suggests a number of changes to the Trustees' report's demographic and economic assumptions. Demographically, the Technical Panel assumes lower fertility rates, slightly higher net immigration, lower disability incidence, and lower mortality improvement than the Trustees. These changes roughly cancel each other out.

Economically, the Technical Panel recommends assuming a lower unemployment rate, a lower labor force participation rate, lower interest rates, lower inflation, slower wage growth, and a lower share of taxable earnings than the Trustees assume. These changes account for all of the factors that worsen the view of Social Security’s fiscal health, the equivalent of a 0.9 percent of payroll larger 75-year actuarial deficit. In previous reports, it was demographic factors that accounted for more pessimistic Social Security projections – a sign that we’re moving more fully into an aged economy.

Despite their variance, all three estimates are cause for concern. Social Security is between 13 and 16 years from insolvency, at which point benefits would be cut across the board if nothing is done to align the program’s revenues with its outlays.

One solution, Representative John Larson’s (D-CT) Social Security 2100 Act, would close the 75-year shortfall by eliminating the taxable maximum on incomes more than $400,000, increasing the payroll tax rate, raising the income threshold for the taxation of benefits, and combining the old-age and disability trust funds while also increasing benefits across the board, strengthening minimum benefits, and increasing annual cost-of-living adjustments. Alternatively, lawmakers could adopt a pro-growth approach recently authored by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget's Marc Goldwein, Maya MacGuineas, and Chris Towner. And finally, you can make your own Social Security solvency plan by using our simulator at SocialSecurityReformer.org.

Numerous policy mechanisms exist to push Social Security towards solvency. Lawmakers need to come together to find a pro-growth and sustainably solvent solution to Social Security’s financial woes before it gets too difficult to do so.